What Killed Ghost in the Shell

Paramount domestic distribution chief Kyle Davies has told CBS News that he believes widespread charges of whitewashing partially impacted the box office underperformance of director Rupert Sanders’ American Ghost in the Shell (GitS) motion picture. Davies may be correct that pre-release controversy diminished some degree of viewer enthusiasm for the film, but the casting of American actress Scarlett Johansson in the title role of Major Motoko Kusanagi is not actually an objective, internal contributor to the film’s weakness. Approval of Johansson’s casting from GitS creator Masamune Shirow, 1995 film director Mamoru Oshii, and widespread Japanese societal ambivalence toward the very concept of “whitewashing” are irrelevant because the opinions of foreigners on American viewers are insignificant in practical effect. The live-action GitS movie suffers from a number of significant flaws, but the accusation of whitewashing should not have been one of them. One of the core underlying themes of the Ghost in the Shell franchise is the proposition that when human consciousness and individuality, essentially the “ghost,” can exist independently of a physical body, visual identification of ethnicity is no longer relevant. Furthermore, to its credit, the live-action GitS movie even directly explains Motoko’s ethnicity, as it visibly appears in the film, logically and narratively invalidating claims of whitewashing. Rather than whitewashing, the flaws the cripple the live-action Ghost in the Shell film include the film’s re-written origin story, alteration of Section 9, alteration of theme, and emphasis on visual design over demographic.

The biggest problem with the live-action Ghost in the Shell movie is its decision to give the Major an original back-story inspired by RoboCop. Rupert Sanders’ film draws direct inspiration from all four anime iterations of Ghost in the Shell. The American film is ostensibly a remake of Mamoru Oshii’s 1995 film. The “geishabots” are drawn from 2004’s Innocence. The antagonist Kuze is based on the character Hideo Kuze from the 2004 Stand Alone Complex 2nd Gig television series. The red leather outfit that Major “Mira Killian” wears during the nightclub scene in the live-action film is inspired by the 2013 Ghost in the Shell: Arise OVA series. So limiting the scope of Motoko Kusanagi’s characterization in the live-action film to strictly the 1995 movie is illogical. The Japanese anime franchise, particularly the “Stand Alone Complex” TV series, establishes that Motoko Kusanagi has lived within cyborg “shells” practically since birth. The “Arise” video series confirms that Motoko Kusanagi earned her military rank “Major” by serving in the army. The “Arise” video series also reveals that Motoko Kusanagi earned her reputation as “Fire Starter,” a master computer hacker, through years of experience and activity. However, the live-action film strips Kusanagi of all of her integrity. In the live-action film, she gets transferred into a cyborg body as a young adult and begins serving in Section 9 less than a year later. All of her tactical skills are presumably implanted in her rather than learned. The live-action film gives viewers no evidence whatsoever that “Major” is any more skilled at internet “diving” or hacking than anyone else. Her title “Major,” in the live-action film, wasn’t earned; it was presumably arbitrarily bestowed upon her. “Major” doesn’t signify an earned rank of status; now it’s simply an artificial codename. Even further weakening the live-action film, when the heroine finally asserts her true identity, discarding the false “Mira Killian” identity, she still identifies herself as “Major,” instead of as “Motoko Kusanagi.” In effect, she tries yet fails to repossess her own identity, choosing to retain the artificial title assigned to her. In effect, the Major of the live-action film is not a self-made woman. She’s not a fiercely independent and capable leader who has proven herself under fire countless times. She’s not a feminist role-model, a female who equals and surpasses her male counterparts in fair comparison. She’s literally a product manufactured by a rich white man. The live-action film gives viewers no reason at all to respect the Major apart from the fact that she’s the film’s protagonist. She’s sympathetic, but being pitiable doesn’t make her worthy of respect or admiration.

In addition to weakening the Major’s innate characteristics, the film also weakens Section 9. Aramaki of the anime is a knowledgeable, shrewd political tactician and negotiator. Three-quarters of the live-action film give viewers a chief of Section 9 whose only qualification is his title. Even when he is finally depicted as formidable, the live-action Aramaki isn’t threatening because he’s brilliant or because he’s politically-connected. He’s threatening only because he’s willing to exert amoral violence. In every anime iteration of GitS, Section 9 has been all-male excepting the Major who leads the team. The “Arise” OVA series even details Kusanagi forming the team to her own specifications. Kusanagi demonstrates her superiority by being a woman commanding her male co-workers. She forms and leads Section 9 because she’s the most capable member of the team. However, in the live-action film Kusanagi is one of, if not the most recent addition to the team. She’s a rookie instead of being the leader. Furthermore, the live-action film introduces an original female member, Ladriya, who not only undermines Kusanagi’s unique position as the lone superior female on the team, she literally serves only as Batou’s human pack animal in the live-action movie.

Regrettably, one of the most fascinating philosophical themes of the Ghost in the Shell manga and anime gets contradicted within the live-action film. All of the Japanese GitS anime proposes the idea that advancements in digital technology will inevitably outpace the evolution of human ethics. At best, the GitS source material proposes that technology is good. At worst, the GitS anime exhibits ambivalence toward technology. While viewers may respect Togusa’s rejection of cybernetic enhancements, the rest of his society views him as a Luddite. The GitS anime demonstrates that technology may be used for nefarious ends, but technology itself is not harmful or bad. The live-action film, however, overtly questions whether technology is “good” in the early scene when the African president poses his blunt philosophical questions then overtly suggests that technology is bad when it reveals that Motoko herself formerly wrote manifestos opposing technology. The movie criticizes technology as something superfluous that merely allows us to consume more alcohol. Furthermore, when Kuze invites Motoko to join him in a bodiless existence in the web, he clearly suggests that such evolution is limited to only he and her, that technology is a private refuge for an elite few. The live-action film is hopelessly conflicted when it’s overtly a film about the potential of technology to remove human limitations yet under the surface it’s a film that suggests that surpassing humanity is wrong.

To its credit, the live-action Ghost in the Shell film has a remarkably tactile appearance thanks in part to Weta Workshop’s exceptional in-camera effects. Sequences including the optical camo chase, Kusanagi scuba diving, and the spider tank duel are marvelously faithful to their source material. Small details including Togusa’s reliance on a revolver and Batou taking care of a basset hound are admirable fan service. However, the film is so preoccupied with capturing the visual design of GitS that it forgets to nail the tone and pace. Particularly Ghost in the Shell (1995) and Innocence (2004), which are the live-action film’s primary inspirations, are methodically paced movies. Arguably both movies are slow, deliberate art-house films. Rupert Sanders’ Ghost in the Shell doesn’t have the slow, intellectual pacing of Ridely Scott’s cyberpunk masterpiece Blade Runner, although it arguably should. It doesn’t have the brisk and action-oriented pacing of summer blockbusters. Sanders’ Ghost in the Shell doesn’t contain very many action scenes, and those which it does include aren’t tremendously exciting or pulse-pounding. The live-action Ghost in the Shell simply doesn’t know who its target audience is. The movie isn’t atmospheric, intellectual, and artsy enough to satisfy fans of foreign, independent and arthouse films. It’s neither exciting nor quite accessible enough to satisfy viewers looking for disposable escapist entertainment. The film isn’t even faithful enough to its source material to completely satisfy the small contingent of anime otaku.

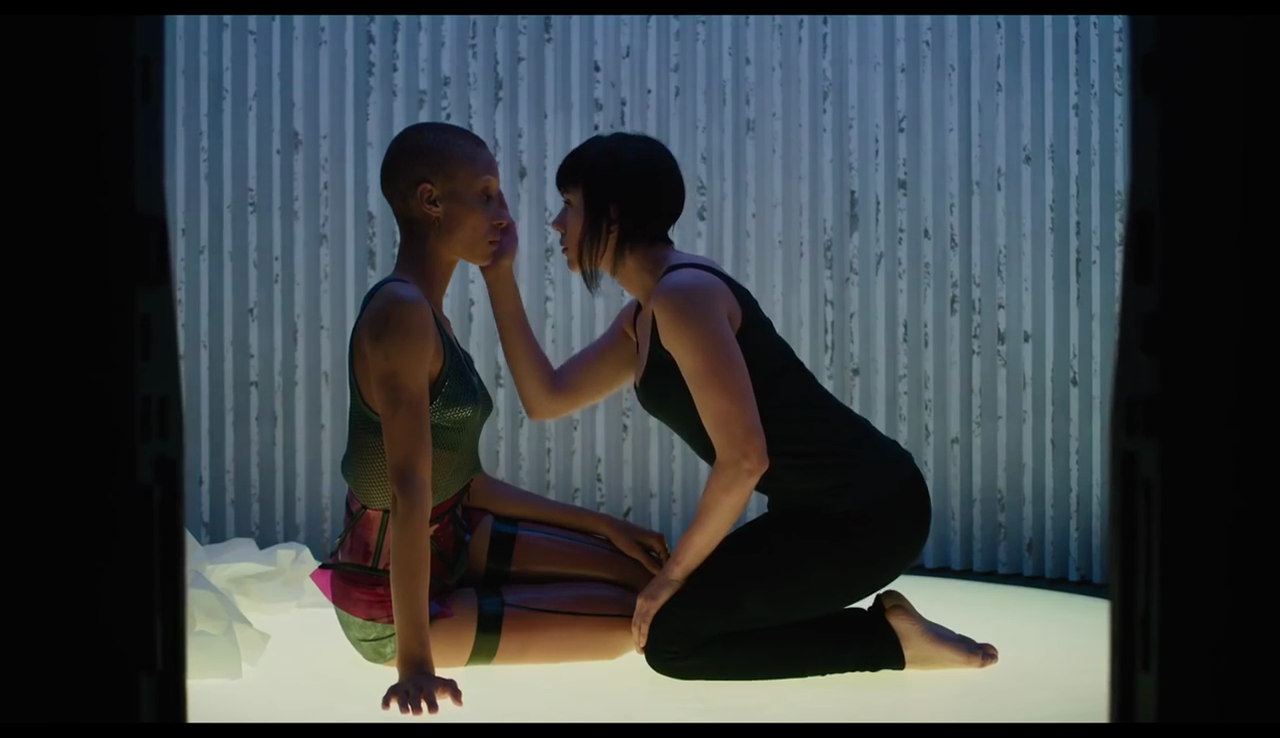

The movie is not a complete failure. The visual design is impressive and looks better on a big screen than a smaller computer monitor. Two sequences within the film particularly hint at what the film could have been. The scene in which the Major silently examines a human prostitute is a haunting sequence that deftly implies “Mira Killian’s” fascination with what makes humans human. The scene provokes viewers to question the Major’s sexual orientation, her interest in sex at all, and more importantly her curiosity about life and what exactly constitutes a living human. Shortly later in the film the Major responds to a question from Batou by sarcastically flipping him the bird. That momentary scene is the film’s only concession to the Major’s sense of superiority. Particularly the Stand Alone Complex and “Arise” anime include numerous scenes in which the Major plays practical jokes on her men or sarcastically illustrates her cynical sense of superiority. That brief moment in the film makes the Major seem more alive and more human than any other moment in the entire live-action film. The movie would have benefitted from more of that snarky superior attitude that reminds viewers that Motoko Kusanagi is the best there is at what she does.

Given the fact that the live-action Ghost in the Shell’s story literally explains exactly why the Major is named “Mira Killian” and has an adult white woman’s body (keep in mind that she was built and maintained by white male corporate president Cutter and white female Dr. Ouelet), accusations of the film whitewashing are a bit unrealistic and unreasonable. However inappropriate, the charge of whitewashing and the controversy which the accusation generated in public discourse may have had some depressing effect on the film’s box office take. But the film simply suffered from numerous other subtle and not as subtle flaws and weaknesses that hampered its box office potential, perhaps the most egregious being the fact that the movie was a moderately faithful remake of a cult film, a film which, since 1995, has always had more respect and praise than viewers. The live-action Ghost in the Shell wasn’t a philosophically challenging intellectual cyberpunk thriller; it was RoboCop 2.0. Yet at the same time the live-action film wasn’t based on the more action-oriented, crowd-pleasing Stand Alone Complex. Neither Mamoru Oshii’s, Kenji Kamiyama’s, nor Kazuchika Kise’s Ghost in the Shell anime have ever been blockbuster hits. Ghost in the Shell has always been a highly praised and respected niche title. Had the American film walked in the footsteps of Blade Runner, attempting to be first and foremost a thoughtful, speculative film, it may have succeeded with critics. Had the film taken most of its inspiration from Stand Alone Complex or the Arise Alternative Architecture motion picture, it may have been a thrilling, exciting crowd-pleasing action film. But Rupert Sanders’ film decided instead to walk the middle-path that appealed strongly to no one.