The Wrong Way to Write About Using Healing Magic

The nature of Japanese light novels is to be simple, easy-reading, disposable literary entertainment. By design, light novels are only barely more literary than manga comic books. Moreover, light novels are typically rapidly written first drafts featuring the barest minimum of editing. Thus light novels frequently contain errors in narrative continuity, technical composition errors, and other minor flaws. What they lack in literate, artistic substance they compensate for with creativity and entertainment value. The “isekai” sub-genre, stories about characters whisked away to unfamiliar new worlds, has arisen as one of the most popular genres of Japanese fantasy literature, especially since the early 1990s. The abundance of stories within the isekai genre naturally distills into more praiseworthy and admirable literary works including the Mushoku Tensei and Sword Art Online franchises, especially poorly written novel series including Isekai Meikyuu de Harem wo and Tate no Yuusha no Nariagari, and everything in-between. While not terribly poorly written, the first volume of author Kurokata’s light novel The Wrong Way to Use Healing Magic falls into the vast and deep well of mediocre isekai fantasy novels primarily because the entire book is nothing more than an extended and particularly dull prologue.

The trope of a protagonist being accidentally caught up in an isekai hero summoning ritual has been utilized in other light novel series including Miya Kinojo’s Chillin’ in Another World with Level 2 Super Cheat Powers, Yuka Tachibana’s The Saint’s Magic Power is Omnipotent, and Ren Eguchi’s Campfire Cooking in Another World with My Absurd Skill. Unlike comparable titles that apply a unique, creative twist, the first novel of The Wrong Way to Use Healing Magic regrettably doesn’t do anything unique or compelling with its scenario. In fact, the novel does very little at all.

Three Japanese high school students are magically teleported to a sword & sorcery world to defend the Llinger Kingdom from invasion by the Demon Lord. But only two of the transposed students were targeted by the summoning spell. The story’s protagonist, Ken Usato, is an unintended extra caught up in the mix. However, his status as a “plus one” has no impact on the story development. Within the first novel, the three teen heroes spend their time training to strengthen their magic casting abilities. Then the Demon Lord’s army begins its invasion. Then the novel ends. Lamentably, the novel contains almost no action whatsoever although the story is not a slice-of-life fantasy. The novel’s intriguing title, “The Wrong Way to Use Healing Magic,” has practically no relevance to the novel’s story. Characterizations are superficial and minimal. Protagonist Usato introduces himself as someone with no hobbies. Yet, seemingly contradictorily, shortly later he refers to himself as having a “gamer’s brain.” He’s also oddly, consciously homophobic for no explained reason. His male upperclassman Kazuki Ryusen is pure-hearted and described as “innocent.” Usato’s female classmate Suzune Inukami functions half-heartedly as comic relief in a story that’s doesn’t need any. She’s also a bit difficult to empathize with since she’s characterized as a girl who pities herself because she’s too good at everything she tries. The only other significant character in the novel is Rose, Usato’s mentor. While she does get one detail of background, she functions more like a prominent supporting character than a main character.

As if the novel knows that its narrative development is thin and boring, the novel tries to inject sub-plots and nuance, but the efforts are irresolute and perfunctory. Halfway through the novel, the story introduces animal mascot characters although these characters don’t do anything nor serve any narrative purpose. As if resorting to cliché, the novel’s first chapter drops the revelation that the Llinger Kingdom treats healing magic users as useless trash, evoking the treatment of the Shield Hero in the Rising of the Shield Hero novels, yet as soon as it’s mentioned, this plot point is forgotten. Knight Commander Siglis announces that he has a matter to discuss with Rose, yet when he goes to meet her, he says nothing of significance to her. In a brief passage a fox girl relays a prophecy to the protagonist. Then this plot point receives no further development. The novel introduces a threatening black knight yet doesn’t bother to give him a name nor have him do anything prominent. In fact, the entire novel’s world building is perfunctory at best. The novel’s magic system essentially gets no detail or explanation. The country neighboring the Llinger Kingdom is simply referred to as “neighboring country.” The demon lord has no name or motivation beyond, “Demon Lord.” The briefly appearing bandit leader is such a cliché that he comes across as a parody instead of a legitimate character.

The narrative also contains other continuity errors. Rose has only one eye, yet the novel contains the descriptive lines, “All I could do was avoid meeting the eyes of this woman who savagely smiled at me,” and, “All I knew was that her eyes were filled with contradiction.” In the first half of the novel Rose makes multiple similar statements including, “If someone dies, revive ’em.” Yet later in the book Rose asserts, “If you die, you’re done for,” and, “I know I can’t bring my boys back to life.” Usato describes the palace’s training ground as “a big open space,” yet then says, “While I was scanning the area, I saw a black-haired girl in the corner of the room.” What room? He’s outdoors.

Other flaws within the novel may arise particularly from the English translation. At one point Rose asks, “Capiche?” without explanation for why this resident of an alternate world would be familiar with Italian language. Similarly, the black knight says, “My bad,” which seems like a distinctly Earth expression used by a character presumably not from Earth. The translation contains numerous minor errors in punctuation and capitalization, but most casual readers won’t notice them. The novel is expressed in the first-person perspective typical of light novels except for one brief scene that switches into third-person perspective. Frustratingly, the novel regularly switches narrator without notice or signal. In at least one occasion the reader must read at least six paragraphs to figure out that the storytelling has shifted to a different character’s point of view.

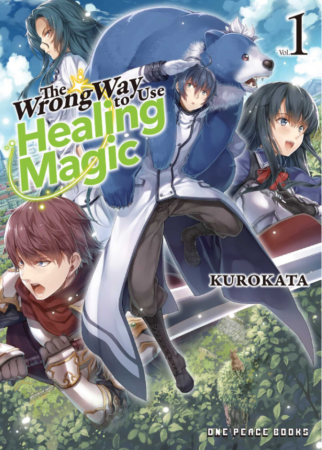

The novel contains no references to nudity or sex and only brief description of graphic violence. The translation includes a few instances of “Sh*t,” one “god*mnit,” and one “son of a b*tch.” The translation also retains Japanese honorifics when appropriate, including “senpai,” “-chan,” and “-kun.” The novel also includes a reference to “tsuchinoko” that may be unfamiliar to readers lacking awareness of Japanese folkloric monsters. One Peace Books’ official English translation of the first novel includes a double-page color character introduction illustration, a color page illustration of the black knight, eleven monochrome illustrations by artist KeG, and one monochrome character concept design illustration.

The isekai fantasy sub-genre can be highly entertaining because it can be very immersive and very gratifying. Readers interested in dipping their toes into the field should be advised to begin elsewhere. Die-hard fans of the isekai genre who are willing and prepared to read everything they can may find some satisfaction from The Wrong Way to Use Healing Magic. Thanks to passable writing, the novel isn’t completely awful; however, while this series may become more exciting and interesting in subsequent volumes, the first novel is 219 pages of redundancy and almost nothing happening.