Reflections on Sasurai-kun

I’ve typically never been highly enthused by any anime created by either of the Fujiko Fujio team. Typically their manga and subsequent anime adaptations have either felt redundant, for example Umeboshi Denka, Jungle Kurobe, and Biriken; particularly child-oriented, for example Doraemon, 21 Emon amd Mojako; or rather heavy-handed, like Warau Salesman and Pro Golfer Saru. So I began watching the 1992 Fujiko Fujio A. no Sasurai-kun series motivated only by intellectual curiosity, just to see first-hand what the show was like. After the ten-minute first episode, I was curious to see what direction the narrative would take in the second episode. After the second episode I committed myself to watching the entire short series. Unlike the most well-known anime titles from Fujiko A. Fujio & Fujiko F. Fujio, Sasurai-kun is a lighthearted, nostalgic anime for adults. The series’ narrative focus wanders a bit and struggles to find a consistent target, yet the show also does a commendable job of depicting the sepia romanticism of lonely souls encountering each other for fleeting moments, and capturing for posterity a nostalgic sentiment of Japanese life that’s probably now largely extinct.

The first of the series’ thirteen episodes introduces Sasurai, a hapless, overworked and existentially lonely salaryman with a crush on his attractive co-worker simply because she’s considerate of him and is the attractive woman he sees every day. One day, on his way to work in a packed commuter train, he bumps into the laughing salesman Fukuzou Moguro who recognizes that Sasurai-kun needs a mental break. So Moguro magically transports Sasurai-kun to a forced vacation in a rural Japanese hot-spring village. When Sasurai-kun finds all of the local inns booked, he ingratiates himself into a tour group of businessmen that have booked an onsen hotel for the evening, shrewdly securing lodging and dinner for the evening.

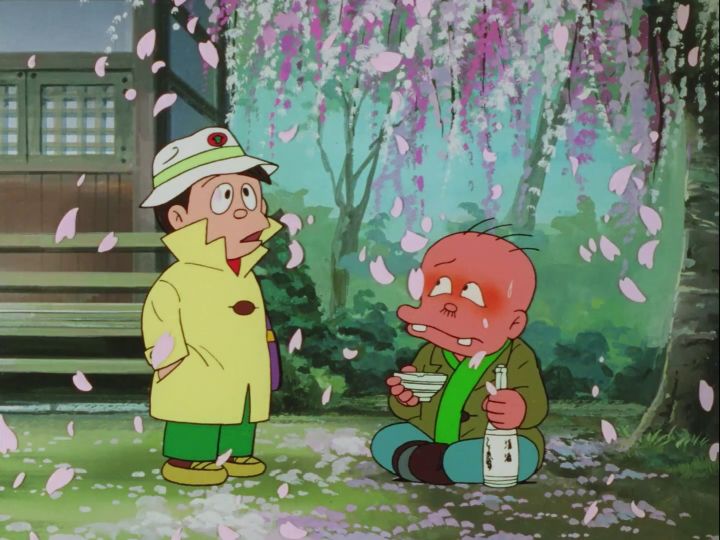

The series’ second episode begins with Sasurai waking from a nightmare about his office job. But the morning sunshine reminds him that he’s on vacation, so he tours the town and runs into a drunken elderly man who promises him a cushy job. Imagining potential good fortune, Sasurai-kun keeps the old man company, bar-hopping while paying the tab. The episode wraps up with a tragic revelation that dashes Sasurai-kun’s hopes, establishing the pattern to the series that as often as circumstances work in Sasurai-kun’s favor they also work against him.

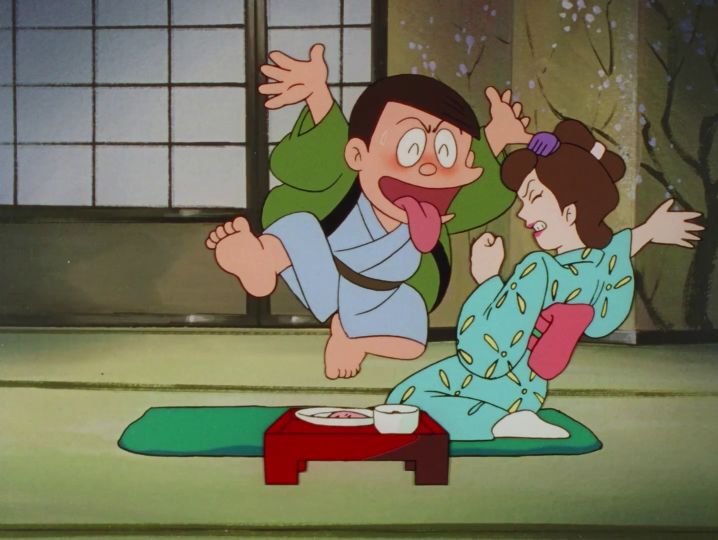

From episode 3 onward Sasurai-kun somehow adopts the new life of an aimless, independently wealthy wanderer. The show never again refers to the office job Sasurai-kun abandoned, nor does the show ever suggest that he’s unable to continue funding his permanent vacation tour of rural Japan. Rather, the narrative emphasis of the show slightly changes. I don’t know whether the first two episodes represent the show finding its direction or if the story took a turn after the first two episodes, but episodes three, four, and five revolve around Sasurai-kun trying to pick up a girlfriend. Episode four is especially noteworthy because it depicts working-age adult Sasurai-kun pining after a high school girl that reminds him of a romantic interest from his youth, and him getting drunk on whiskey during a drinking party with a trio of high school boy ruffians.

In episode six, as if to purge women from his brain, Sasurai-kun makes a futile effort to become a Buddhist monk. In episode seven he encounters a fellow former salaryman who has forsaken society and resorted to a sort of Tarzan-esque wild lifestyle.

Episode eight prominently introduces the romantic sentimentality of the lonely old soul wandering solitary streets, drowning sorrows in neighborhood izakaya, and the sad irony of missed opportunities and ships passing in the night. Much of the visual imagery in this episode is striking and among the best of the series.

Episode nine again begins with Sasurai-kun waking from a nightmare, this one about Sasurai-kun finding himself alone and unmoored in a faceless, impersonal world of transitory relationships. In this episode he once again blends into a tour group for a night. This tour group is a collection of urbanites getting a taste of life and work on a farm, except the farmers clearly view the tourists as nothing more than exploitable temporary labor, resulting in some situational comedy.

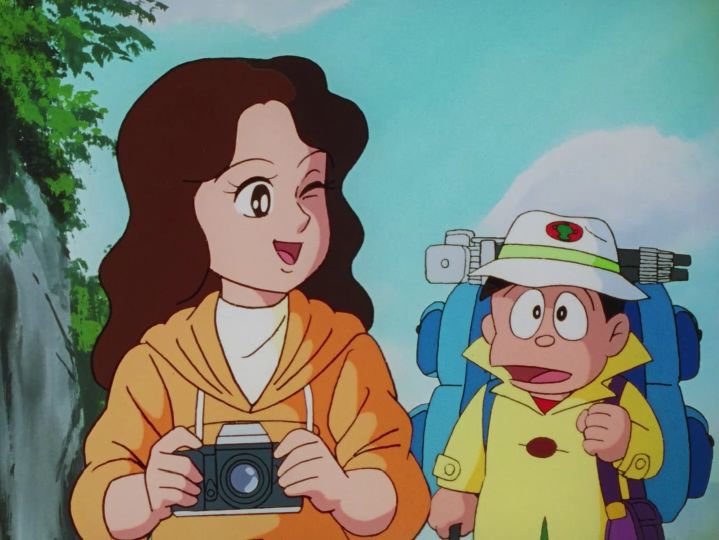

Episode ten introduces a bit of automobile action in the form of Sasurai-kun getting a ride from a young woman unwisely learning to drive a stick-shift on narrow mountainous roads. Subsequently Sasurai-kun meets an amenable, attractive nature photographer who suggests that they visit a local hot spring together. Predictably, her goals are a bit different from his, however.

Episode eleven takes place on trains and introduces details that were doubtlessly contemporary at the time but feel nostalgically dated now, including public water fountains that dispense folding paper cups, and sleeper train cars.

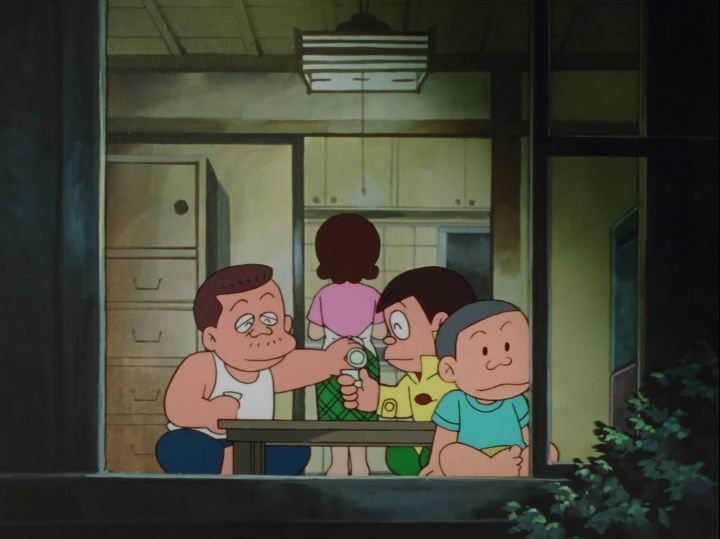

Episode twelves heightens the sense of Japanese nostalgia. Sasurai-kun referees a neighborhood kids’ baseball game. At sunset, as the kids go home, one of them realizes that Sasurai has no home to return to so brings the wanderer in tow. Without any questions, the boy’s drunken father and suffering mother welcome the guest as if he was a family member. When the saké runs dry, the perturbed father storms out of the house angrily, dragging Sasurai along to a nearby izakaya bar. As the father drinks himself into a stupor, the son comes to fetch his old man, announcing that dinner is ready. The considerate Sasurai-kun carries the father back home and has a pleasant family dinner with the boy and mother. That evening, Sasurai-kun dreams of his own mother. Then he quietly departs in the dead of night so as not to further impose on the family.

The series ends with another episode infused with distinctly Japanese flavor. Disappointed to find that the view of Mount Fuji is obscured by civilization, Sasurai-kun encounters a local man who promises to provide a better view. The man then proceeds to lead Sasurai-kun to a nearby public bath with a wall mural of Mount Fuji. The man introduces himself as a novice aficionado of traditional sento public baths. The elder “master” of touring sento then arrives and proceeds to take the increasingly exhausted Sasurai-kun on an artistic tour of Japan by visiting various public baths with interior landscape murals. When Sasurai-kun finally arrives at a beautiful bath with a panoramic natural scenic view, he settles in to enjoy, but coincidentally the sento master arrives with his own idea of “scenic view” in mind.

Series’ episodes three to five feel a bit redundant with their central focus on trying to pick up women, and subsequently the goal of getting a girlfriend never entirely seems to leave Sasurai-kun, but the bulk of the back half of the series feels like a more expansive predecessor to Tetsuko no Tabi. The show is a good-natured, relaxing slice-of-life comedy that doesn’t star high school girls and isn’t moé. And like a version of Tamayura that isn’t about high school girls, Sasurai-kun gives viewers a perspective on rural, suburban, and traditional modern Japan apart from bustling Tokyo. The art design is simple yet detailed enough to be evocative and effective. As the show premiered in 1992, it’s still proximate enough to the golden age of anime that it occasionally includes some noticeably creative shots such as this view from a train window.

Sasurai-kun isn’t intended to be a show for everyone. It’s a sedate mixture of sitcom and drama delivered in succinct installments to put a wry smile on the faces of weary adult viewers. Especially in the contemporary era of anime designed either to sell discs & character merchandise or shows aiming to be provocative or bold, Sasurai-kun is a pleasant slice of retro entertainment that doesn’t feel especially dated. It’s a short, simple little overlooked gem that shines because of its gentleness and mild humor.