Read Only Acquisition Memory

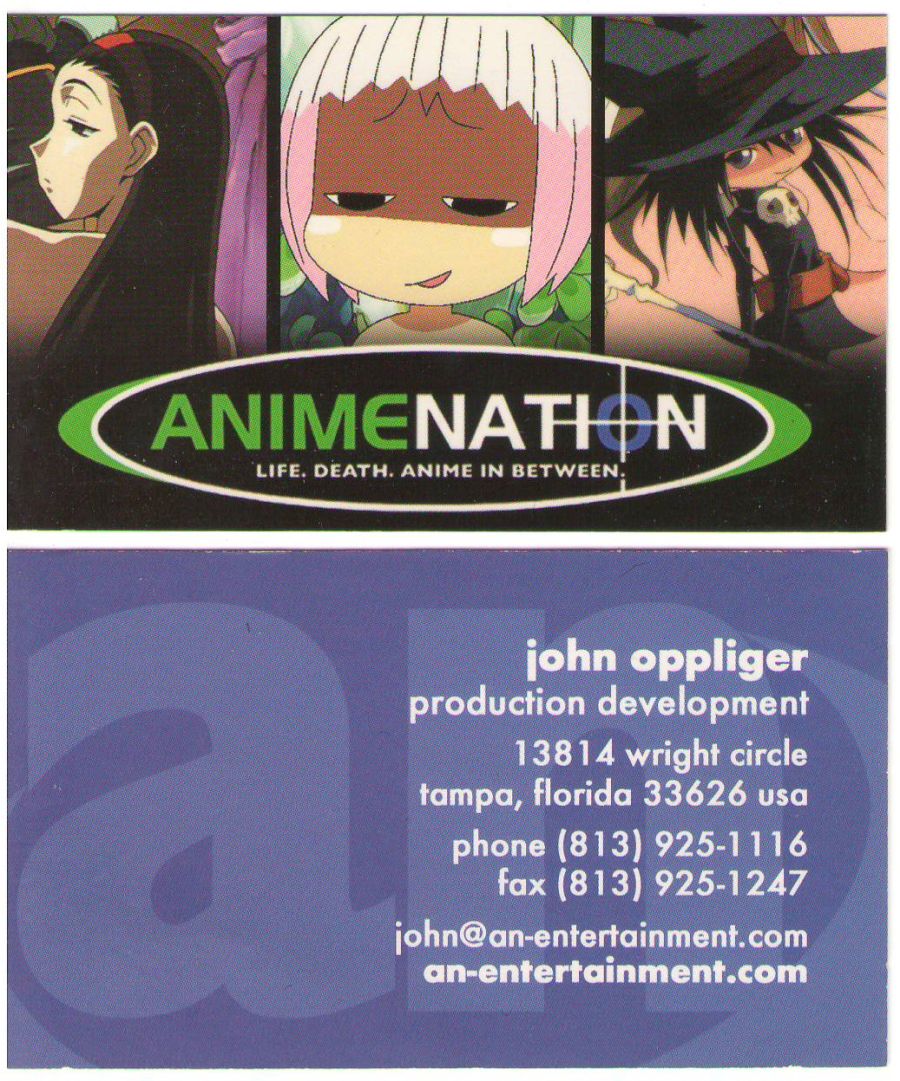

For little reason in particular I thought to myself that perhaps some people may find interesting or curious my select and limited memories of AN Entertainment’s experiences with anime licensing in the early 2000s.

In a certain sense, it’s true that we “tried” to license the 1998 Berserk television series. At the time, we were merely entertaining the idea of possibly entering the licensing game. We made an inquiry about the cost of the series. When the answer returned, it was so far out of our means that we never spoke of the possibility again.

We contracted Coastal Carolina Sound Studios for the English dub of Miami Guns. Coastal founder Scott Houle encouraged us to partner with his studio to acquire the rights to Madhouse’s 2004 series Monster, based on the Naoki Urasawa manga. I don’t recollect exactly why a partnership never happened, probably cost. Eventually Viz acquired the TV series license but only released a dozen of the 74 TV episodes.

I repeatedly pestered Gene, the AnimeNation co-founder and CEO, to inquire about the availability of the Azumanga Daioh television series. Gene hesitated and delayed. By the time he finally asked, the answer came back that AD Vision had just signed a deal for the show.

I remember looking at the first publicly released character designs for Bakuretsu Tenshi published in the monochrome newsbriefs section of NewType magazine. I said to my co-workers, “Somebody’s going to make money off this.” FUNimation acquired the title.

Gonzo sent us, and presumably many other companies, a publicity packet for its tentative feature film Afro Samurai, based on self-published manga by Takashi Okazaki. The concept and early production designs seemed promising, but Gonzo was seeking a one-million dollar contribution in exchange for distribution rights and limited producer input. That amount was way out of our means. Note that at the time Afro Samurai was planned as a single motion picture. Eventually the production was divided into three OVAs, and both FUNimation and actor Samuel L. Jackson got prominently engaged with the production. Sadly, I’m uncertain of whatever happened to that two-page solicitation flyer.

I distinctly recollect receiving a similar color publicity release about Artland’s Yugo ~Koushoujin~. I looked at the single anime key art image, read the series summary, and immediately announced, “Nobody’s going to buy this!” AD Vision bought it. Then I bought the three AD Vision DVDs for my own collection when they nearly immediately went on clearance sale.

We received a VHS tape containing the first episode of the 2004 television series Yumeria. I didn’t think it was a strong, promising first episode and said so. We declined, but AD Vision bought it.

TBS sent us a licensing sample tape of the 1997 Ganbare! Goemon television series. I watched the tape in the AnimeNation break area and delivered my professional recommendation to Gene. “It’s way too Japanese,” I said. “Nobody’s going to buy this.” AD Vision bought it and to their credit even released all 23 episodes.

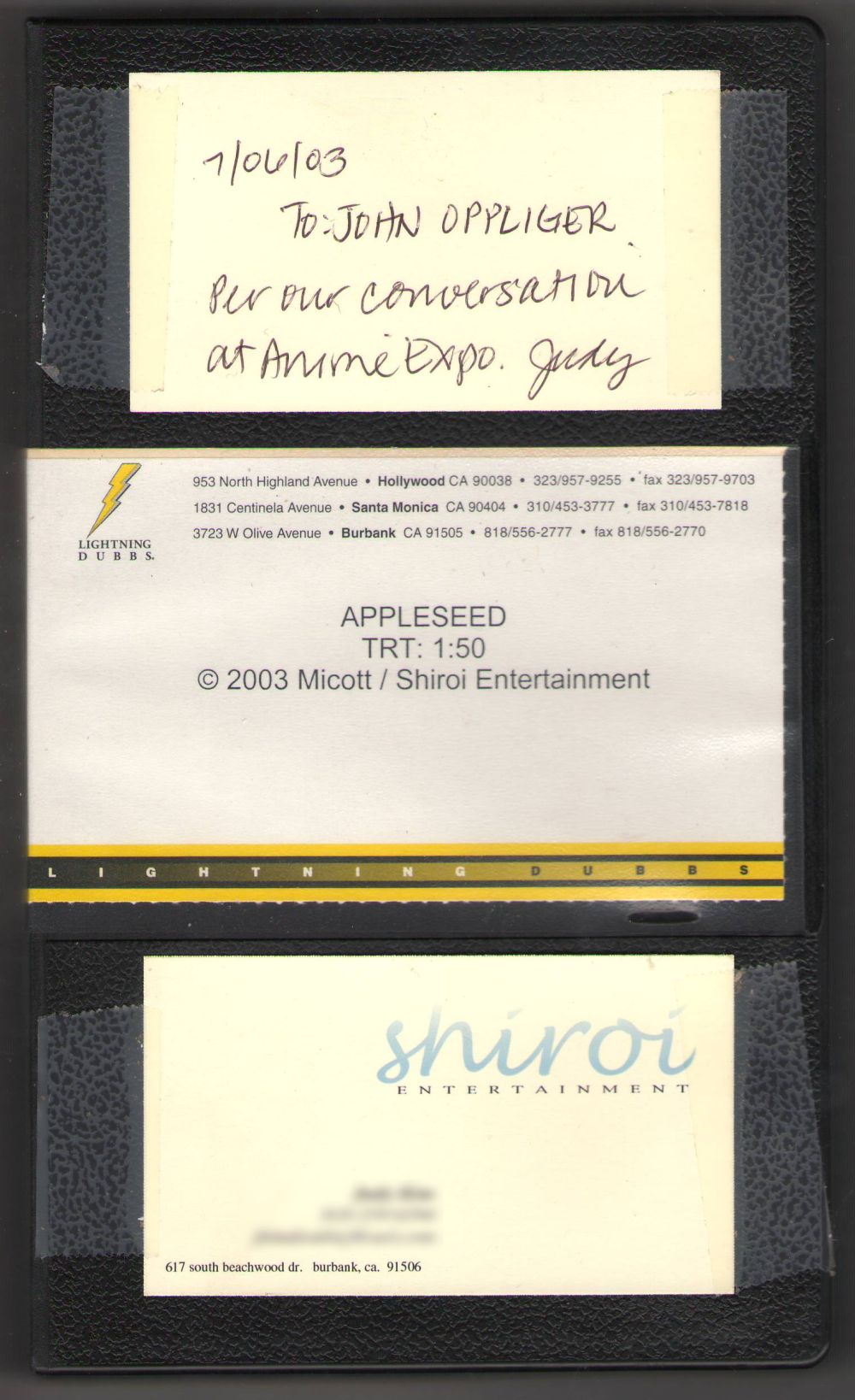

Evidently in the summer of 2003 I had a conversation regarding the possibility of licensing, or perhaps it was just promoting, Toho’s forthcoming full CG Appleseed motion picture. I don’t recollect this particular conversation at all, but I have the tape to prove it happened.

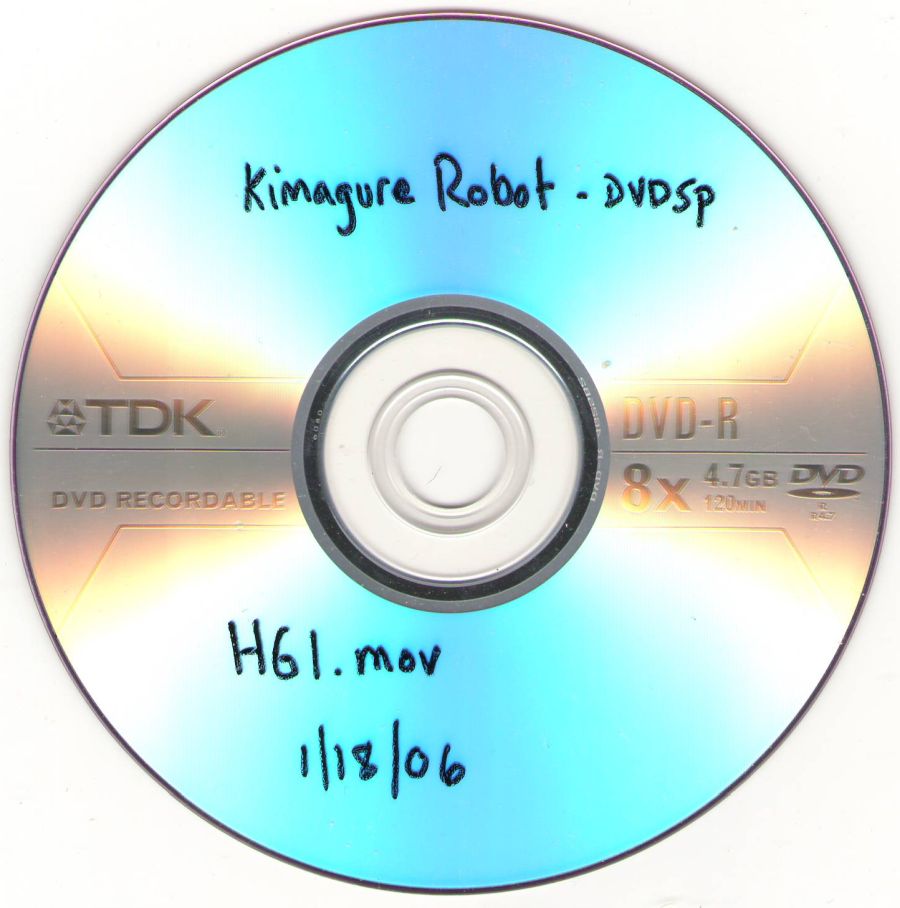

Production studio 4°C wanted assistance from an American distributor to get its web anime series Kimagure Robot into American circulation. In 2006 the studio sent me a disc copy of the mini-series, a disc which I still have. By that time licensing anime hadn’t made us rich, so Gene was very gun-shy about entering another licensing and production agreement. So despite my enthusiasm over the possibility of becoming a business partner to Kouji Morimoto’s animation studio, a deal never progressed.

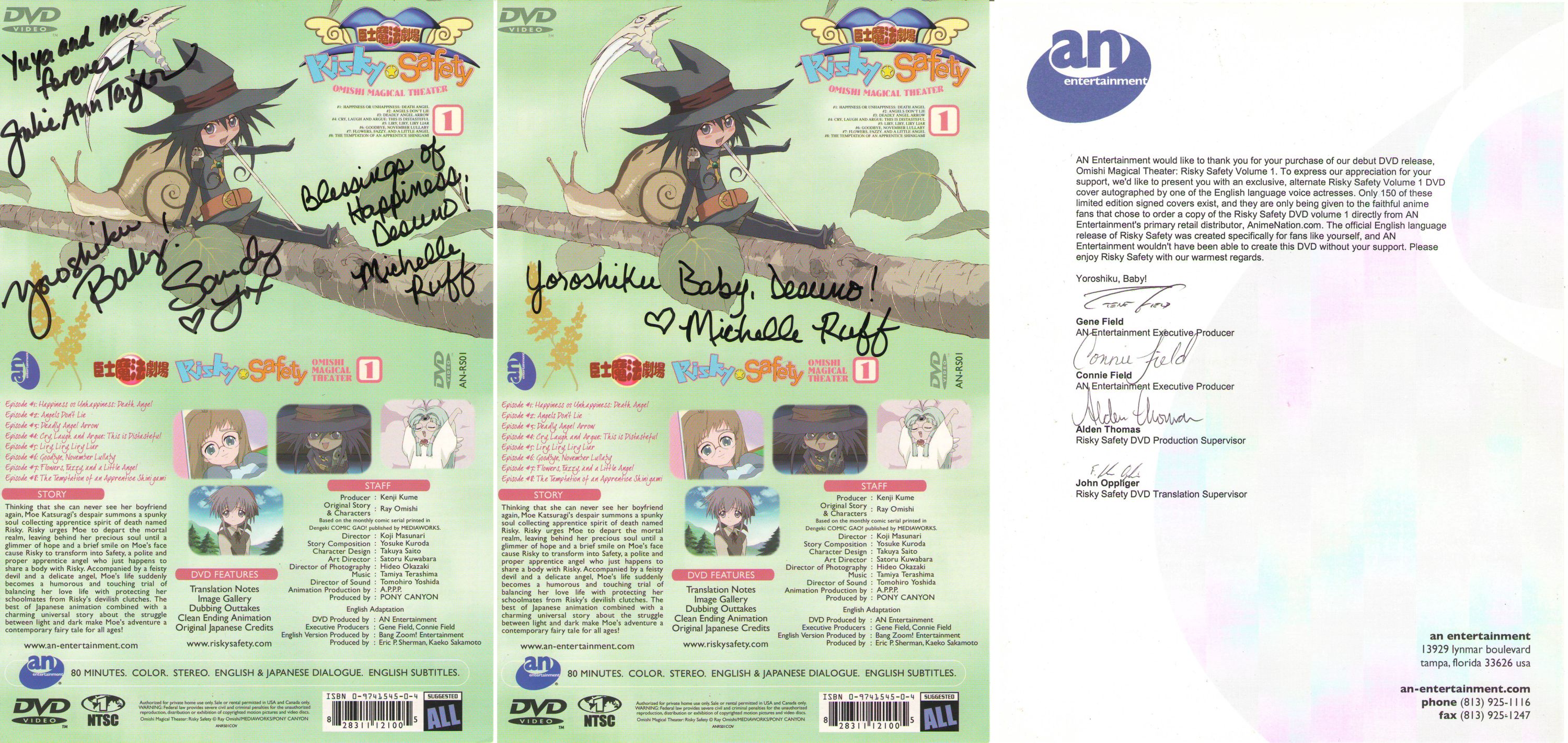

When Animation began to seriously consider licensing anime, we quickly narrowed our targets to a pair of short series from Pony Canyon. Having no prior experience in translation, video mastering, replication, or distribution, we wanted to cut our teeth on something of manageable length: a single series of 13-minute episodes. I suggested Omishi Mahou Gekijou Risky Safety and D4 Princess because they were both short series, and I’d watched the entirety of both: Risky Safety via VHS Sachi’s fansubs and D4 Princess via untranslated VHS copies of Japanese TV broadcasts. The AnimeNation staff collectively and distinctly preferred Risky Safety. As of today, D4 Princess remains unlicensed for American release.

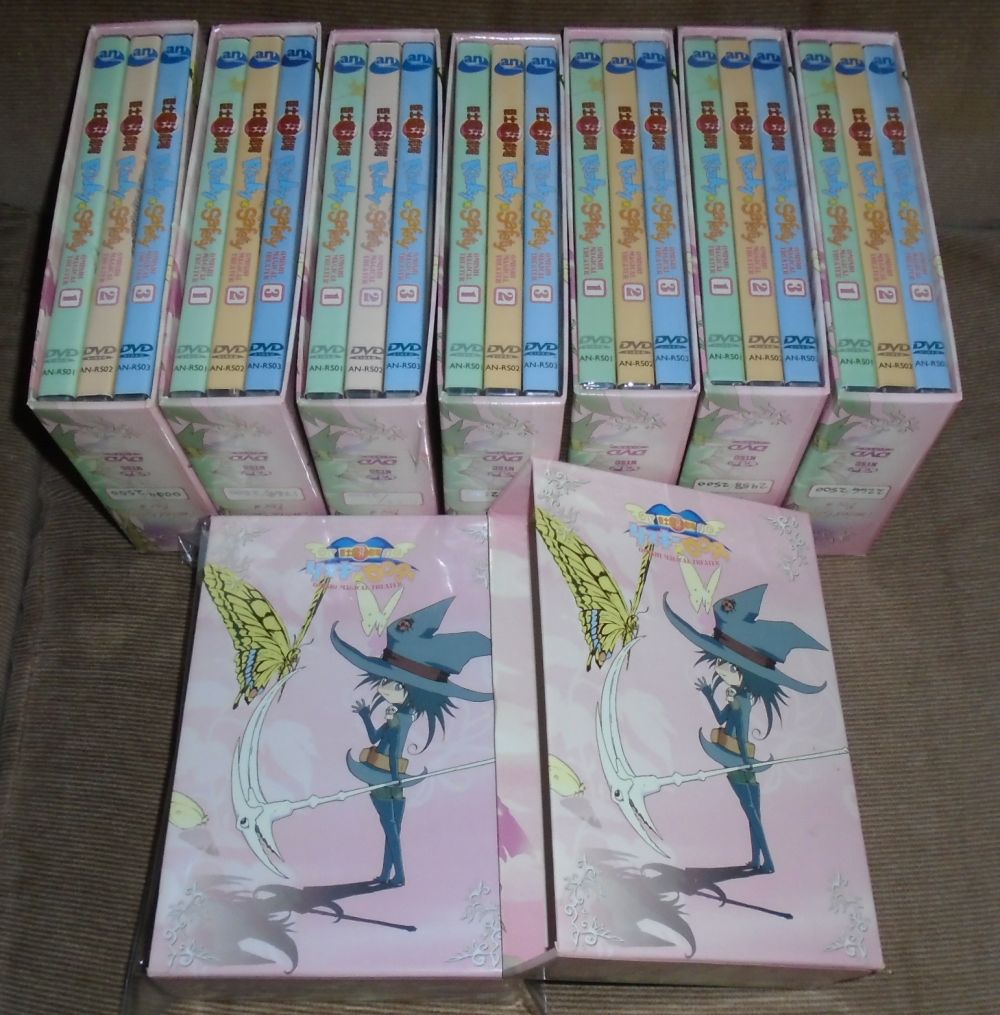

I received permission from “Sachi” to use her fan translation of the series’ dialogue as the basis for our official script. The original Japanese DVD release was six discs with unusual horizontal, rather than vertical, cover art printed on heavy stock paper rather than typical gloss paper. In order to stay as faithful as possible to the Japanese release, we printed double-sided covers for each of our three American DVDs using the same original Japanese cover illustrations and using the same heavy stock paper. We also had a limited number of covers autographed by members of the Bang Zoom! dub. AnimeNation customers that pre-ordered the DVDs or purchased the first disc immediately upon release received the DVD, a separate autographed cover, and a hand-signed letter of gratitude for the support from the AN Entertainment staff. The first 2500 copies of the first DVD were distributed with a free, hand-numbered chipboard box. At the time, no American distributor included the series box without an additional upcharge. Alden Thomas, AnimeNation’s co-art director, hand numbered each box in silver Sharpie.

My collection includes set 4, set 22, and a rare empty box without a serial number.

Some time following the release, Studio A.P.P.P. sent us an offer to purchase the entire pallet of original hand-drawn production art (“genga”) for the Risky Safety anime. We agreed. The shipping pallet covered with boxes sat in the AnimeNation warehouse for a long time. In my recollection, it seemed like at least a year. Multiple times I offered to personally reimburse the cost of the purchase in order to buy all of the art myself. Gene repeatedly rebuffed my offer. Eventually, when AnimeNation was running short of cash, Gene asked Jimmy, Sara, and I to sort the thousands of cuts. All of the pencil art for each shot was stored in a separate envelope. We made stacks of the art by letter grade: the “A” art was large, fully visible character shots; the “B” pile was less impressive yet still prominent character images; the “C” pile was small or obscured shots. Then we selectively withheld some of the nicest “A” cuts for ourselves, mixed the remaining lots of “A” to “C” quality images and sold five-pound lots of genga art to our customers. The lots sold out practically instantly. Years later all of the remaining “D” art that consisted of backgrounds and miscellaneous shots, and most of the withheld “A” art trickled back into my possession.

I’d watched all 12 episodes of Miami Guns via untranslated VHS recordings of the Japanese TV broadcast. I suggested it as AN Entertainment’s second release. In running length it was the same as Risky Safety, so it was an amount of footage that the small AN Entertainment staff could manage. Being a Florida-based distributor, we liked the serendipity of acquiring a show set in the mythical post-apocalyptic reconstructed nation of Miami. (Watch the show. It’s not set in the real-world Miami, Florida.) We loved the show’s extensive parodies of Initial D, Mr. Ajikko, Die Hard, Godzilla, The Matrix, 2001: A Space Odyssey, Yusaku Matsuda, Antonio Inoki. It was an irreverent, goofy series in the vein of the popular Excel Saga. The show met an initial American mixed response of largely, “Huh?” and, “No thanks,” in large part, I think, because it wasn’t a title that the American fan community was already familiar with. To this day we’re still proud of the release and still enjoy the show. While not a major hit in Japan, it was successful enough that manga creator Takeaki Momose got a second series adapted into anime, Magikano, which was subsequently licensed by AD Vision.

Leftover Risky Safety & Miami Guns DVD replicator check discs:

Jungle wa Itsumo Haré Nochi Guu wasn’t extensively fansubbed yet still managed to become quite popular in fan circles. My first encounter with the show was an untranslated capture of the first TV episode in RealMedia format. AN Entertainment was ready to immediately sign a licensing contract for the initial TV series. Bandai informed us that a single producer on the Japanese side personally wanted a bigger royalty check as a result of the license, but he was scheduled to retire in a year. So Bandai insisted that we wait a year before signing contracts so that the producer would retire and Bandai wouldn’t have to pay him a hefty royalty check. Naturally, we spent a year frustrated, but we were so emotionally committed to Guu that we didn’t want to abandon the licensing opportunity.

Our licensing agent in Tokyo suggested that we license an alternate series from Bandai during the interim year just to demonstrate our good faith intention to complete the licensing agreement for Guu. Bandai aggressively encouraged us to license the 2002 series Pita-Ten, based on the manga by Di-Gi-Charat creator Koge Donbo. If memory serves, the asking price was $25,000 per episode for distribution rights. The show had 26 episodes. It was a hard pass for us because at the price the series would never ever be profitable in America. To this date Pita-Ten has never been licensed for American release.

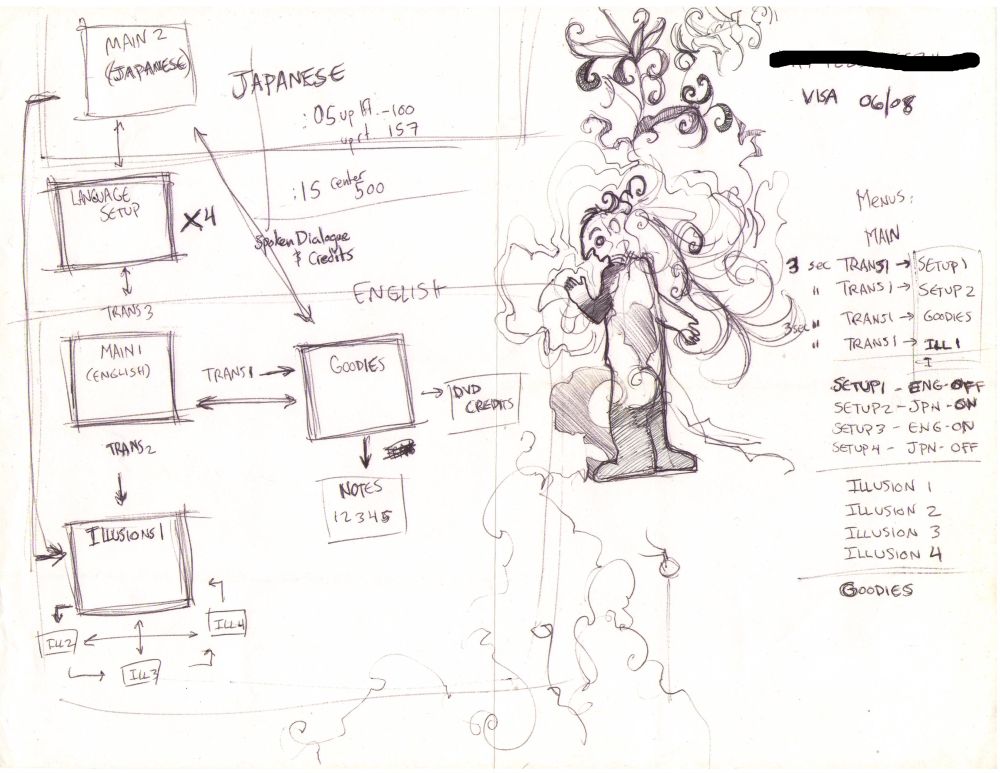

One of Alden’s technical doodles for the layout of the Haré+Guu DVD menu.

There are far more details and stories, but either I’ve forgotten most of them, or they’re details that I don’t feel inclined to expound just yet.