I Hear the Sunspot -Limit- 3 Review

Yuki Fumino’s subtly complex, resonant, and heartfelt dramatic manga series I Hear the Sunspot premiered in 2013 and has sporadically extended into five ongoing collected books. The touching series is ostensibly about the intimate friendship that develops between a pair of college classmates, one of whom suffers from hearing loss. Taichi Sagawa is a brash, outgoing young man that wears his heart on his sleeve. His progressively deepening friendship with handsome yet withdrawn Kohei Sugihara comes to define the lives of both young men, leading them to revelations and changes in their lives and increasing awareness of themselves and their relationships within modern Japanese society. The relationship between Taichi and Kohei evolves from classmates to a status like platonic lovers, soulmates who constantly struggle to match and intertwine their complimentary opposite wavelengths. At the same time readers follow the life struggles of these two young men, readers can also extrapolate a subtle and incisive observation of Japanese culture that has a well-intentioned yet incomplete awareness of the physically disabled and handicapped.

Fumino’s initial I Hear the Sunspot story was contained in a single volume. The success of the initial volume led to the 2015 publication of a single-volume sequel, I Hear the Sunspot: Theory of Happiness. The series continued in a 2016 third volume, I Hear the Sunspot: Limit that spanned three books. One Peace Books will release the official English translation of the third book of I Hear the Sunspot: Limit on April 13, 2021. The most recent installment in the “Sunspot” story broadens its narrative focus compared to the earlier volumes, paying closer attention to Taichi, Maya Oukami, Ryu Chiba, and, at last, Taichi’s grandfather. The third book of “Limit” reserves its focus on Kohei until its second half, placing readers into the same confused, uncertain space that Taichi resides in following Kohei’s abrupt suggestion that the two young men avoid seeing each other. Both Maya, first introduced in “Theory of Happiness,” and Ryu, first introduced in “Limit” book one, receive their most substantial character development and explication in this concluding third book of “Limit.” Both characters, who may have come across as slightly under-developed supporting characters in the previous volumes, get fleshed-out stories and nuanced personal motivations in “Limit” book 3. Likewise, Taichi’s grandfather, previously only an abstract reference in prior books, becomes a fully realized member of the cast in “Limit” book 3. Readers who had previously only known Taichi’s grandfather through Taichi’s own descriptions are finally introduced to the elderly man and learn that he, like everyone else in the cast, is a much more dynamic and developed human character than previously assumed. Kohei’s mother, also previously just a supporting character, even gets her own opportunity to assert herself and escalate into a prominent role among the supporting characters. And, of course, the story continues to evolve and deepen the relationship between Taichi and Kohei by splitting them apart as never before and establishing that even separated their concern and affection for each other only draws them closer together.

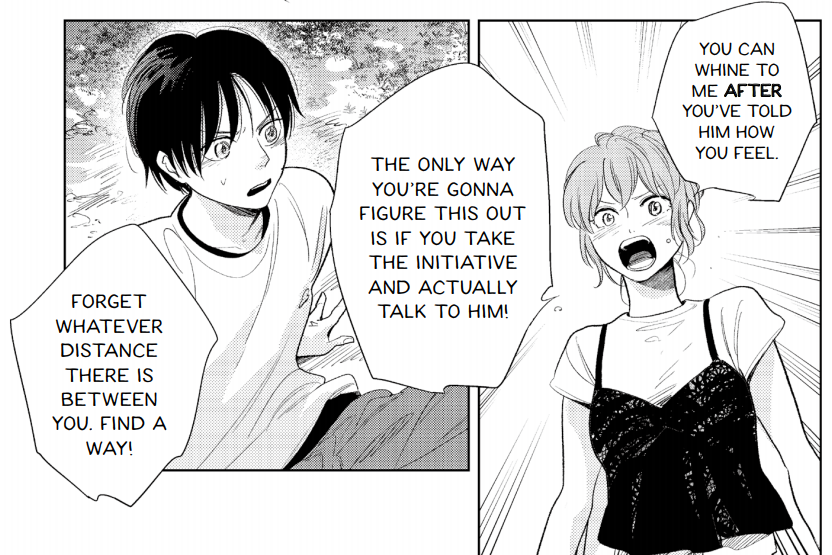

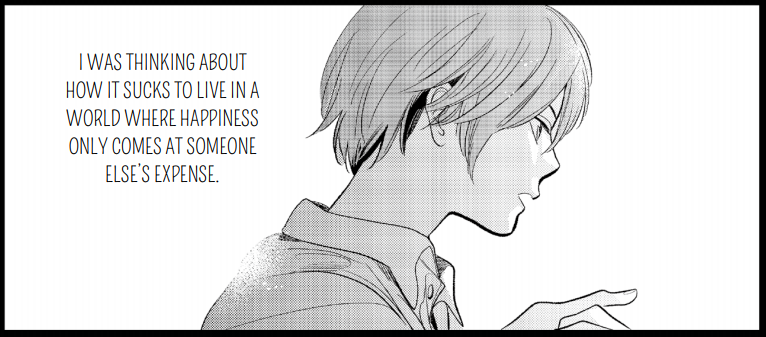

Also of particular fascinating note, the detailed depiction of Ryu’s history and personal struggles along with the careful depiction of Taichi’s work with his new employer, a company that hosts corporate disability awareness training sessions, drives home author Yuki Fumino’s underlying social critique in which hearing loss stands as a metaphor for Japanese society’s lack of full and forthright communication. The series’ earlier books did deal with personal actualization and fulfillment. An aspect of the story that’s highly compelling is the intense focal emphasis on personal revelations, understanding one’s own desires, and finding one’s own path through life. But the thematic focus shifts in “Limit” book 3 to an observational critique of Japanese society. Unlike American society, and a story revolving around American characters that would typically depict characters’ efforts to fulfill their own ambitions and emotional needs, I Hear the Sunspot: Limit book 3 establishes that its characters’ greatest vulnerabilities are their compassionate concerns for their loved ones. Especially Taichi, Kohei, Maya, and Ryu suffer emotional angst because they value the happiness and fulfillment of their dearest friends and family above their own. However, their own empathy prevents them from fully understanding the very circumstances they seek to espouse. The individual characters represent the larger contemporary Japanese culture that aspires to deliver happiness and equality to all of its citizens, yet since physical disability is a somewhat taboo subject of discussion, everyone mis-perceives what happiness and personal fulfillment actually mean for other people. A supporting character who means well suggests that the disabled associate only among each other, as only those of similar experience can fully comprehend and empathize with each other. Yet separate but equal is not equality since exclusion is the opposite of understanding and acceptance. This currently final volume of “Sunspot” teaches its characters that being overly considerate is just as emotionally damaging as being too inconsiderate. The ability to talk to each other, even about painful, difficult, or embarrassing subjects, even when the communication is difficult, is what allows for understanding, personal growth, and ultimate happiness.

Upon first impression, the third book of I Hear the Sunspot: Limit may feel less narrowly focused and a bit less intimate than the prior books. But the climax of “Limit” is no less heartfelt than any of the prior chapters. Yuki Fumino deliberately widens the storytelling focus to provide some degree of narrative closure for all of the manga series’ primary characters. The story also widens its perspective in order to better address the larger thematic point of the story. Hearing loss, and by extension all physical handicaps, become less a characterization detail and more of an aspect of living in a social society that all people have to accommodate, understand, and appreciate. After making that point, the manga returns to its narrowed focus on the developing co-dependent relationship between Taichi and Kohei, illustrating both the earliest and most advanced points of the two young men’s association. By the end of the book readers will certainly find the current conclusion of the I Hear the Sunspot story just as affecting, incisive, and remarkably truthful as it’s always been. For these characters, what matters most is their personal realities, their personal relationships, sense of commitment and responsibility rather than a more conventional platitude for the reader’s consumption. That deep, intimate honesty is what makes the lightly romantic drama feel so real and compelling.

I Hear the Sunspot may be casually referred to as a boy love romance, but the story is far more accurately an interpersonal relationship drama starring characters who see past gender to care so deeply about one another that they unconsciously hurt each other with kindness. Each revelation, each confession revealed deepens relationships yet moves the characters closer to completely sharing their fears, hopes, and desires with each other. The more the characters communicate, the more they have built up that needs communication to each other. So the reader builds deep empathy with each of the characters as the reader sees what private thoughts each character has that ought to be spoken and shared, but which the characters themselves are hesitant to reveal. Thankfully, at the same time “Limit” volume 3 drives all of the cast members’ revelations and relationships the farthest they’ve come so far, their lives continue, so the volume concludes with the open possibility that Yuki Fumino will return to pen another chapter in this ongoing dramatic story.