Ask John: Why is Sailor Moon Such an Iconic Success?

Question:

What makes Sailor Moon such an iconic global franchise among anime fans, despite other magical girl anime sharing similar traits such as action-oriented plots, drama, in-depth world-building and characterization, romance, and an elegant aesthetic? In other words, what sets Sailor Moon apart from other anime in the genre?

Answer:

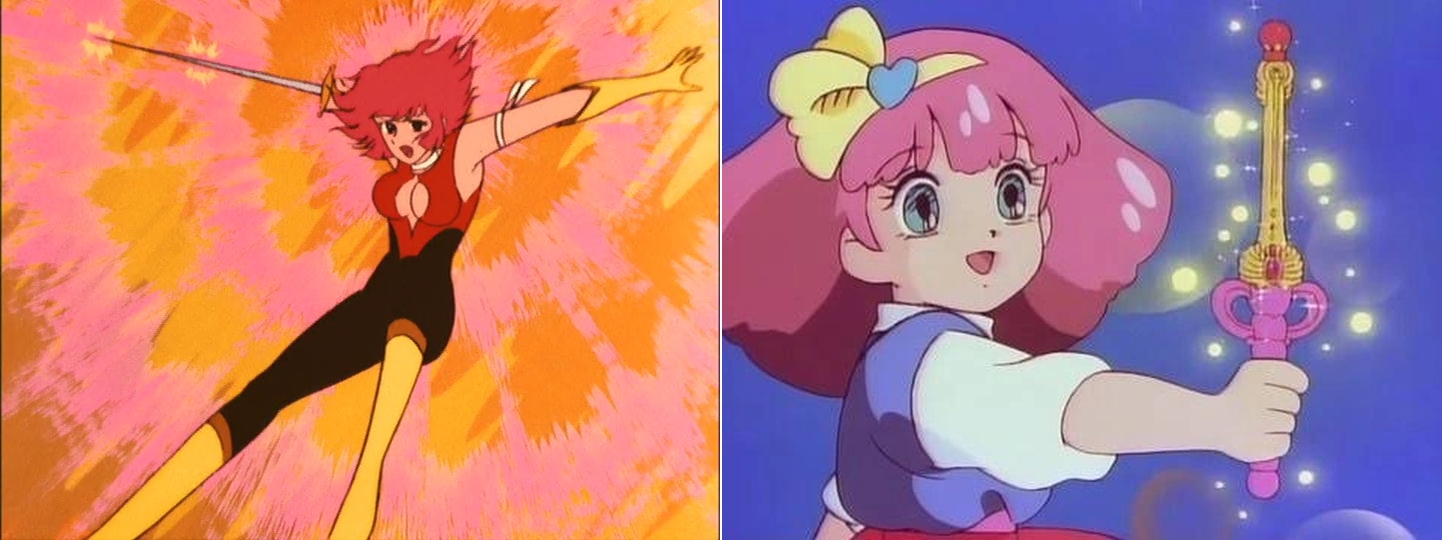

The reason for the immediate and lasting success of the Sailor Moon franchise is rather simple. Creator Naoko Takeuchi introduced some of the core concepts of Sailor Moon in her 1991 manga series Codename: Sailor V. The Codename: Sailor V manga introduced Minako Aino, her magical companion cat Artemis, and the moon symbology. Yet the series rested comfortably within the tropes and expectations of the traditional magical girl fighter genre that had existed for the prior twenty years. Most prominently, Sailor V descended from Go Nagai’s Cutey Honey (1973) and Takeshi Shudo’s Magical Princess Minky Momo (1982). These two earlier series helped introduce the scenario of a young girl fighting to defend the world from a diabolical evil.

Just four months after debuting Codename: Sailor V, creator Naoko Takeuchi was struck by the inspiration to remake the story with a different influence. Takeuchi rebooted Sailor V as Pretty Soldier Sailor Moon by turning the new series into a shoujo version of Tatsuo Yoshida & Tatsunoko Production’s 1972 anime series Kagaku Ninja-tai Gatchaman. Color-coordinated hero teams based around a unifying theme had been popular for twenty years. Unexpectedly, Masami Kurumada’s 1986 manga and anime series St. Seiya had developed a massive Japanese fan following among women. Despite the graphic violence of St. Seiya, young Japanese women were drawn to the series’ effeminate character designs and flowery aesthetic. Naoko Takeuchi realized that no one had seized the opportunity to transform the girlish-looking boys of St. Seiya into literal girls. The bronze saints’ “cloths” armor was revamped into the familiar Japanese sailor-fuku worn by countless Japanese school girls. St. Seiya’s zodiac constellation theme was marginally revised into a lunar theme, and thus the tremendously successful St. Seiya franchise, which itself was a variation on the concept introduced by Gatchaman, evolved into Pretty Soldier Sailor Moon.

Yet Naoko Takeuchi deserves further credit for creating an ideal formula with Sailor Moon. Not only was the core concept of pretty color-coordinated fighters in themed armor already a proven successful trope, Takeuchi applied the traditional conventions of shoujo manga, drawing the characters as wispy, doe-eyed lasses and injecting a prominent dose of romantic angst that would give readers and viewers an additional dramatic angle to chew on.

The predictable immediate success of the Sailor Moon franchise quickly spawned imitators including Ai Tenshi Densetsu Wedding Peach (1994) and Tokyo Mew Mew (2000). But while successful in their own rights, neither Wedding Peach nor Tokyo Mew Mew did what Sailor Moon had done. Although both Wedding Peach & Tokyo Mew Mew were shoujo manga stories, neither emphasized a romantic sub-plot to the extent that Sailor Moon did.

In retrospect, the breakthrough success of Sailor Moon was obvious. Sailor Moon was fundamentally a gender-swapped relaunch of a genre trope that had already proven massively successful multiple times before. Moreover, creator Naoko Takeuchi didn’t just re-tread previous concepts. She wholeheartedly transitioned an established shounen manga scenario into the shoujo manga vein. No one had so boldly created a hybrid of that sort before Naoko Takeuchi, so the combination of novelty and inspired creativity turned Sailor Moon into something simultaneously familiar and popular and also fresh and strikingly unique. Takeuchi did such a good job of exploiting and hybridizing influences that the original 1991 Sailor Moon franchise has supported both live-action and next-generation animated remakes that still rely on the characterizations, scenarios, and combination of themes that Takeuchi perfectly incorporated into her original manga.

On a side note, a similar hybridization of established concepts didn’t occur again until 2004 when Ojamajo Doremi creator Izumi Todo, Dragon Ball Z director Daisuke Nishio, and Toei Animation transitioned the tropes of the live-action Super Sentai franchise into the shoujo genre by creating the Pretty Cure franchise which has now dwarfed even the popularity of Sailor Moon largely due to its conceptual flexibility of allowing for rotating casts.

While Sailor Moon touched a nerve with Japanese viewers by mining two established, popular, and successful concepts – the costumed hero team and the emotionally conflicted shoujo drama, the Sailor Moon franchise also quickly garnered international recognition and cult following because the story was so uniquely novel and distinctly Japanese. Western viewers, particularly those in Europe and America, had never seen anything like Sailor Moon. The girls in sailor suits felt very familiar to Westerners. After all, the Japanese sailor fuku was originally a Western import. But the visual aesthetic of pretty girls in mini-skirts shooting magic blasts and fighting monsters was so drastically different from any cartoon that European or American audiences had ever seen that Sailor Moon immediately became a unique fascination for otaku outside of Japan.