A 9 for 9 Love Stories

The golden age of Japanese anime lasted from roughly 1980 through 1992. The era coincided with Japan’s economic bubble period during which countless investors flocked to funding anime productions, allowing animators and directors an unprecedented period of creative freedom. That particular creative freedom partially manifested itself through a variety of anime productions that emphasized tone, atmosphere, and visual expression: Tenshi no Tamago, Robot Carnival, Machikado no Märchen, TO-Y, Arei no Kagami, Twilight Q, Gosenzo-sama Banbanzai, X Densha de Ikou, Birth. Introspection and solemnity also emerged as prominent themes during the era. Popular shounen action television series such as Sengoku Majin Goshogun and Yoroiden Samurai Troopers were continued with morosely psychological dramatic sequels in the form of the Étranger movie and “Message” OVA series. Arriving at the tail end of the golden age, the anime anthology film Ai Monogatari 9 Love Stories capitalizes on both of these period trends.

Animated by studio Animate Film, the studio best known for animation including 10 Little Gal Force, Antique Heart, Dog Soldier, and the original 1991 Heroic Legend of Arislan, the production studio isn’t one commonly associated with exceptional animation work. Yet the Ai Monogatari movie does feature very strong animation thanks to the involvement of acclaimed segment directors including Koji Morimoto, Mamoru Hamatsu, and Hiroshi Hamasaki. Because the film is so subdued and dialogue-oriented, the animation isn’t flashy and is frequently easy to overlook. This film, based on short manga stories by acclaimed manga-ka Kaiji Kawaguchi (Eagle, Silent Service), typically receives negative reviews from western critics. Anime News Network’s Justin Sevakis said that the film, “Misses the mark almost entirely.” The singular review on RateYourMusic gave the film a .5 out of 5. Just the opposite, I found the movie quite gratifying and enjoyable, I think, because I immediately understood what the film was and what it wanted to accomplish. Particularly as a product of its era, Ai Monogatari is an effort to evoke tone, to capture the bittersweet melancholy of love challenged by contemporary alienation, anxiety, uncertainty, and regret. Ai Monogatari isn’t a singular love story told in three acts and ending with a happy conclusion. Instead, Ai Monogatari is the anime equivalent of a somber blues croon drifting through a smoky lounge, or a wistful lover staring into space and wondering what could have been if the past had worked out differently.

The film begins with the “Dakishimetai” (“I Wanna Hold Your Hand”) segment directed by Tomomi Mochizuki, creator of Fancy Lala and director of the Orange Road & Maison Ikkoku movies. Like all of the shorts in the film, this initial segment challenges viewers. The segment takes place mostly in flashback when teen boy Tatsuo hesitates to act on his crush on classmate Saeko. The short segment only drops hints that Saeko faces a troubled life, both as an adolescent and years later as an adult woman. The lonely imagery of two teens sitting besides each other silently, not touching, on a cold, empty beach, speaks volumes about the distance within their relationship. In the segment’s bookend sequences viewers can interpret that both Tatsuo and Saeko have been adrift for years: Tatsuo has lived regretting that he let his opportunity slip by, and Saeko clearly regrets her life choices. The episode concludes, again, with implication, but one that should be easy to interpret.

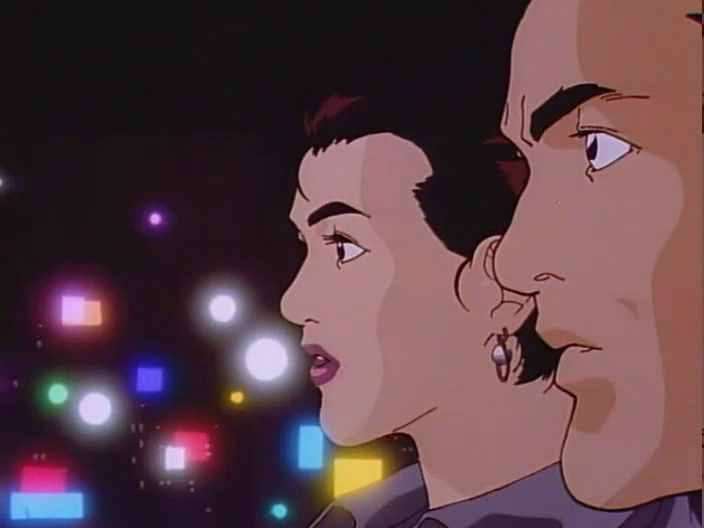

Director Kouji Morimoto’s segment, “Hero,” encapsulates the Japanese pragmatic approach to love. Kei has agreed to an omiai arranged marriage with a man she obviously barely knows. She bumps into her old high school crush, Jun, whom she gave up on out of a sense of moral responsibility. The now adult Jun likewise has a current girlfriend although he’s still haunted by his old affections for Kei and his regrets that during his youth he did what he thought was expected of him and sacrificed his own long-term happiness for the short-term benefit of his teammates. With the wisdom and experience of adulthood, the couple cast aside the rules of society and decide to prioritize their own shared heartfelt desire.

The segment “Yoru wo Buttobase” (“Let’s Spend the Night Together”) is the singular action-oriented and most overt segment of the film. This segment was directed by B.B.Fish and TO-Y director Mamoru Hamatsu. The ironic segment is animated almost exclusively in monochrome to subtly reinforce the viewer’s perception that the story is black and white with one clear perspective only to upend that expectation in the end. The protagonist is an unlikely hero who rescues a tragically victimized woman from a jealous and oppressive domineering boyfriend. Characterization is subtle and sneaky, as the entire episode drops hints that the viewer may not recognize. The protagonist claims to love his one night stand at the same time he’s hurriedly dressing to leave her. To paraphrase Shakespeare, the lady doth protest too much throughout the episode. Ultimately the episode exhibits some attractive art design and slick, detailed hand-drawn animation. And the segment slyly reminds viewers that love is fickle and not always rational.

Regrettably the “Jikan yo Tomare” (“Stop the Time”) segment directed by Shigurui director Hiroshi Hamasaki is the singular weakest episode of the collection because it surpasses subtlety into outright opacity. A troubled man clearly at the end of his wits is drawn back to his hometown where he encounters a woman who may the lover he left behind years before, who subsequently vanished in a boating accident. The segment is deliberately ambiguous about whether or not Eiko is actually Mayumi with a new identity. Unfortunately, the episode also applies the theory that people with amnesia “stop aging” a bit too literally. The segment has the right idea about creating an ambiguous ending in which possibly Mayumi recovers her memories and reunites with her former lover, or perhaps the desperate man finds the strength in “Eiko” to end his own life or possibly even kill her along with himself in a lovers tragedy. The massive polarity in possibilities leaves the short film so wide open that it feels incomplete rather than leaving the climax to the viewers’ imagination.

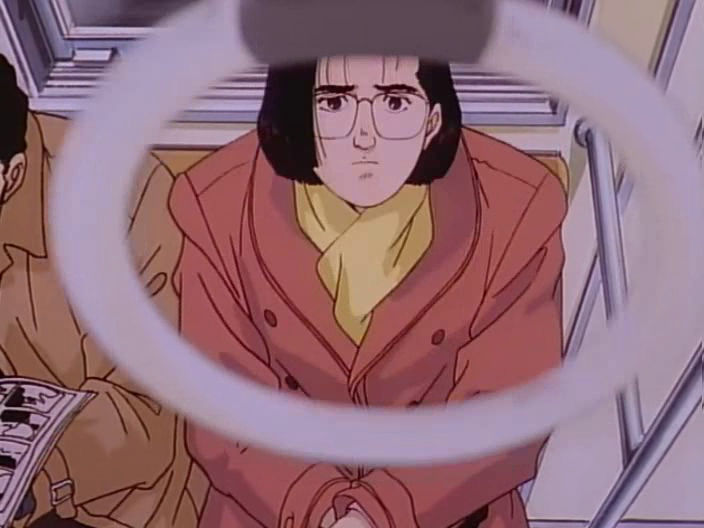

The “Uragiri no Machikado” or “Betrayal in the City” segment was also directed by directed by Tomomi Mochizuki, who directed the film’s first short. Similar in theme to the “Let’s Spend the Night Together” segment, this short piece again is about reversing expectations. The protagonist, a young man who has made a place for himself in Tokyo, the big city, thinks himself now sophisticated and experienced, able to plan out exactly how to handle breaking up with this long-time girlfriend who’s visiting from the countryside. Because the segment provides a running commentary from its protagonist, viewers get to know a bit about his personality. He’s a bit self-absorbed and over-confident, but he doesn’t think he’s inconsiderate. He means well and wants to let his future ex-girlfriend down gracefully. But the short film’s climax once again demonstrates that love sometimes has other plans, and women are not to be underestimated.

The “Ai Sazunirarenai” (“I Can’t Stop Loving You”) segment is an excellent follow-up as it once again even more subtly presents the scenario of a man who thinks highly of himself discovering that he’s vastly under-credited his female companion. Once again, this episode challenges viewers to read between the lines. Hayami is so preoccupied with advancing in his career that he’s initially unable to comprehend other values in life. He concentrates solely on fulfilling the expected obligations of his job, and he plans to marry the boss’ daughter in order to inherit the company. A single brief conversation is all that’s necessary for astute viewers to realize that his fiancé is just as cynical as he is, seemingly a perfect match for him. But his exposure to his co-worker Etsuko’s compassion and humanity softens his heart, ultimately leading him to turn his back on his shallow and unfeeling profession, at the most gratifying moment, and run to the woman who loved him all along yet had the maturity to let Hayami learn from his own mistakes and find the truth of his own heart. The segment’s climax is wordless because nothing needs to be said. Etsuko and Hayami both understand the weight and significance of the moment, just as viewers that have been paying attention should. This segment was directed by Hidetoshi Omori, director of the “Deprive” segment of Robot Carnival and prolific key animator for titles including Kill la Kill, Naruto Shippuden, and Negima!?

Magical Emi, Miracle Girls, and Yokohama Shopping Log director Takashi Anno’s segment “Ano hi Nikaeritai” (“Those Were the Days” or “I Want to Go Back to That Day”) may be the most tragic of the collection while certain as subtle as the rest. The segment revolves around a yakuza boss who develops a romantic interest in a particularly staunch Ginza hostess. Even more that most of the nine stories, this one is characterized by an atmosphere of alienation, loneliness, desperation. The boss recollects his childhood, possibly a moment when he was happiest in his life. Yoko, the segment ultimately reveals, has spent her lifetime waiting for him. Despite his violent temper, she remembers and recognizes the thoughtful man beneath the thuggish veneer. She rejects his efforts to buy her affection because she has pride in herself, and she knows that he’s capable of more honest sincerity. But tragically love proves to be the downfall for both characters as love causes them to drop their guard. This evocative short film, in particular, is heavy with symbolic setting and imagery including rain, dead leaves, blood, and a constant threat of abrupt violence.

The “Lion and Pelican” segment from director Koji Sawai, episode director on titles including Ranma ½, Irresponsible Captain Tylor, and Parasyte, is the film’s most high concept short. The exceptionally well animated segment revolves around a Ginza hostess who spends years as the mistress of a famous professional baseball player. The pro pitcher Takeguchi is a bold, masculine man, straightforward with his opinions and desires. His love affair with Shino is a relationship of mutual satisfaction. His only promise to her is that their relationship will end when he retires from baseball. Shino unsuccessfully and halfheartedly tries to manipulate Takeguchi while Takeguchi ultimately reveals a bit more of himself than expected as well. The point of this segment is the thematic depiction that even when love is commoditized like a contract, it bleeds into emotions and sentimentality. This episode also includes several moments of especially fluid animation.

The concluding segment, “White Christmas,” directed by Iku Suzuki, director of Yumeiro Pâtissière, Princess Rouge, and the original Kodomo no Omocha short film, is arguably the most conventional of the segments. But it serves as a pleasant climax for the collection. Newspaper reporter Kumi chastises her co-worker Kenichi for being lazy and irresponsible. She discovers, however, that he simply has a different but no lesser attitude about life and responsibility than she does. So when he asks her for a date, she responds with an ultimatum, to see whether or not Kenichi can prove himself reliable.

All nine segments of the film star adults who deal with romanticism with adult pragmatism and obstinacy. As is typical of Japanese adults, the characters don’t vociferously express their feelings. Much of their intentions are unspoken, left to the viewer to interpret through the characters’ actions. Every segment, with the exception of “Stop the Time,” presents adequate context and characterization for the viewer to intuit exactly what’s going on. But the onus is heavily on the viewer to pay attention to small clues, to interpret motivations. Little in the movie is bluntly spelled out and overtly obvious. Viewers anticipating typical romantic comedy will be disappointed. Ai Monogatari contains no slapstick, no sitcom outside of the satirical “Let’s Spend the Night Together” segment. Ai Monogatari emphasizes the wistful and disconsolate blues of bittersweet love, of love delayed or unfulfilled, love tinged with sadness. This bittersweet tone is advocated through both the storytelling and the evocative 80’s style visual animation that’s filled with creative, stylish flourishes. Viewers that want and expect the conventional will likely find Ai Monogatari unsatisfying. But viewers who appreciate storytelling that’s a bit more challenging, more subtle and adult, which requires more astute observation and interpretation from the viewer, may find the movie quite fulfilling.