Is Mikagura School Suite Worth Visiting?

Japanese light novels are so called because they’re typically short and superficial. The vast majority are written in first person perspective, allowing for both quick reading and quick writing. In fact, Japan’s voracious hunger for easy reading novels is so demanding that popular light novel authors may churn out new books as quickly as one a month. Such a brisk pace allows for little time to carefully edit or revise, so light novels periodically exhibits errors in continuity or detail. Awareness of the trends behind Japanese light novels and varying willingness to overlook the inherent flaws prone to light novels will largely determine individual readers’ reaction to the first volume of author Last Note’s light novel series Mikagura School Suite.

Mikagura School Suite ~Stride After School~ volume 1 revolves around freshman high school student Eruna Ichinomiya. After passing the entrance exam for the Mikagura High School, Eruna discovers that her new school requires its students to participate in an extracurricular after-school liberal arts club. Moreover, the school’s various clubs “battle” each other for rankings that determine club members’ relative comforts at the school.

To a large degree, a reader’s ability to brook this book will depend on the reader’s ability to abide the protagonist and narrator, Eruna Ichinomiya. Eruna is a whirlwind of contradictions. She’s highly excitable yet believes she’s always calm. She’s unconsciously highly hypocritical. She’s casually and thoughtlessly cruel. She perceives her tremendous irresponsibility and lack of personal consideration to be “cute” character traits. Rather unpleasantly, she weaponizes homosexuality to besmear her cousin’s reputation, yet she takes offense when people presume that she has lesbian tendencies because she’s a teenage girl who fantasizes about romantically pairing with other teenage girls. She also thoughtlessly categorizes “pure Japanese” people as “normal” and foreigners as embarrassing outsiders or unusual novelties. Even more troubling, she doesn’t even acknowledge cute classmates as human beings. In her mind, cute girls are objects for her to collect and fantasize about taking advantage of, not people with unique, individual personalities. In the perception of the favorable reader, Eruna may be cutely deluded. For the critical reader, she likely comes across as sociopathically narcissistic. Eruna is particularly hysteric, the type that says, “It’s no big deal,” while harping over and over on the exact point she claims isn’t a concern. For example, early in the first chapter she claims, “… at least I was self-aware enough to stop myself from going on and on about them [new student welcome parties].” Yet she makes her claims in the middle of a five-page long rant about a new student welcome party. Although Ichinomiya doesn’t especially overuse exclamation points, her rhetoric constantly creates the impression that she only thinks and speaks in bursts of excited shouting that very rapidly become exhausting to read. Eruna is also the sort of narcissist who dismissively refers to others as idiots yet firmly believes in the integrity of her own wistful and equally irrational ideas. In fact, she describes herself: “I sat there whining about whatever came into my head…”

In fact, the novel may likely encourage readers to wonder why Eruna Ichinomiya is the protagonist of the story at all. Apart from being almost maniacally optimistic and self-confident, she has practically no redeeming or admirable qualities. Literally within the novel’s final three pages a climactic plot revelation occurs that predictably confirms that Eruna actually is the exceptional person she’s always believed herself to be, even though she’s done nothing to earn or deserve her exceptionalism. The story does introduce a handful of supporting characters, but all of them get such minimal development that they feel more like plot points or foils for the protagonist to interact with than actual individuals.

Like typical Japanese light novels, the text contains no conventional description or exposition; it’s entirely first person narration. And the narration in Mikagura School Suite is particularly confusing because Eruna Ichinomiya, the narrator, randomly alternates her conversations between thinking to herself and speaking out loud. The result is occasionally awkward because the novel sometimes depicts her as carrying on normal conversations with other characters even though she only speaks limited portions of her dialogue out loud. Alternately, revealing poor editing on the part of the original writer, occasionally other characters respond to dialogue that Eruna only thinks in her mind. Furthermore, on occasion Eruna does speak out loud, but her dialogue has no quotation marks around it to designate it as spoken dialogue.

Even during the rare instances when the narrator does attempt to provide descriptions, the explanations are exceptionally threadbare, such as, “When I opened my eyes the room was just an ordinary room… Far from being an expansive hall, it was just an average, small room. There was little furniture or furnishings, giving it a somewhat desolate appearance that was offset by bold and elaborately patterned wallpaper.” Another example is the statement, “Looking over all the flyers, I couldn’t help but be entertained by the sheer originality of them all,” with no explanation at all about what makes the flyers “original.” Furthermore, the club battles are described with such minimal detail that they’re difficult to even comprehend or envision; they’re literally just described as “choreographed dance motions” or “a special attack from a fighting game.”

Explanation is also lacking for the main character’s description. Literally the only description of her provided by the text is that she frequently has disheveled hair. She seems to have no friends because the text never mentions any friends besides her cousin. And despite Eruna frequently dropping video game related references like using magic points or battling boss monsters, there’s no evidence in the text that she plays video games or even has any hobbies at all.

While Eruna Ichinomiya is prone to exaggeration and self-delusion, periodically her narration also comes across as simply padding for length. Periodically, for little apparent reason, she’ll launch into long, detailed accounts only to then dismiss everything she just said as merely overexcited imagination. For example, “The silence was oppressive to the extent that I could hear the ringing in my ears and the pounding of my heartbeat, which had started to take on a samba-esque beat. Okay, maybe I oversold that a little. It wasn’t really a samba beat. That was an exaggeration.”

The novel also includes other careless inconsistencies. Eruna visits the Mikagura campus to take her admission test and interview. But then several weeks later when she moves to the campus dormitories, she’s surprised to see the campus, as though she’s never been there before.

Story development is strikingly minimal. The first three quarters of the novel covers a span of two days plus a flashback to the day Eruna took her high school entrance exam. The majority of the book occurs during Eruna’s first two days at her new residential high school. Then the final quarter of the book rushes through three weeks of Eruna visiting a variety of school clubs and getting rebuffed by her classmates who become increasingly conscious of her abrasive personality. The novel concludes with Eruna thrust into participating in one of the school’s characteristic club representative one-on-one battles, but rather than depict breathtaking excitement, the sequence is largely underwhelming because Eruna turns most of the “battle” into a game of hide & seek by running away from and hiding from her opponent.

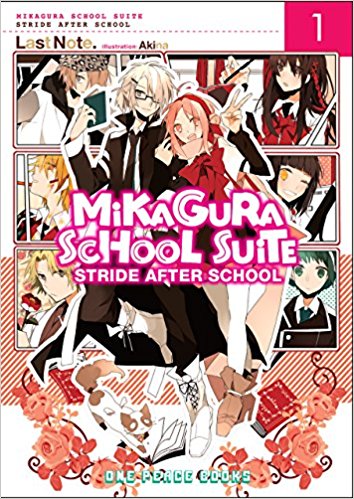

One Peace Book’s English language presentation of the Mikagura School Suite novel is a hefty 320 pages because the book is published with particularly large margins and includes an author’s afterword and a brief glossary of Japanese terms. The English translation reads easily but includes a variety of Japanese terms such as “sempai,” “nii-chan,” “gyaruge,” “chuunibyou,” “kappa,” “chanko nabe,” and “NEET,” most of which are translated in the book’s back-end glossary. The book also includes at least one unexplained reference to Japanese cultural tradition: “They’d dumped salt all over me when I left the building,” a mildly amusing joke for those who understand its meaning. I noticed one evident typo, a “me” that’s supposed to be “be.” The translation also contains numerous technical errors in comma placement, but average readers likely won’t notice. The book includes an initial eight pages of glossy color illustrations and an additional ten monochrome illustrations by artist Akina.

“Mikagura Gakuen Kumikyoku” has spawned eight novels, a six-volume manga adaptation, and received an anime television series adaptation in 2015, so fans of the manga or TV anime may be especially interested in trying out the originating source novel. Furthermore, readers fond of anime franchises such as Baka to Test to Shoukanjuu, Ben-to, Meikaku City Actors, D-Frag, and Yuru Yuri may be tempted to try out this novel as well.