I Hear the Sunspot Review

Manga artist Yuki Fumino’s 2013 debut story I Hear the Sunspot (Hidamari ga Kikoeru) is an intimately personal dramatic expression. The slice-of-life story is subtle, affecting, and quietly incisive. The single volume revolves around college students Taichi and Kohei, young men of opposite personalities but common background who find empathy, respect, and a sort of love with each other. Although originally serialized in the boy-love manga magazine Canna, I Hear the Sunspot is best described as a thoughtful drama with an undercurrent of Japanese social criticism.

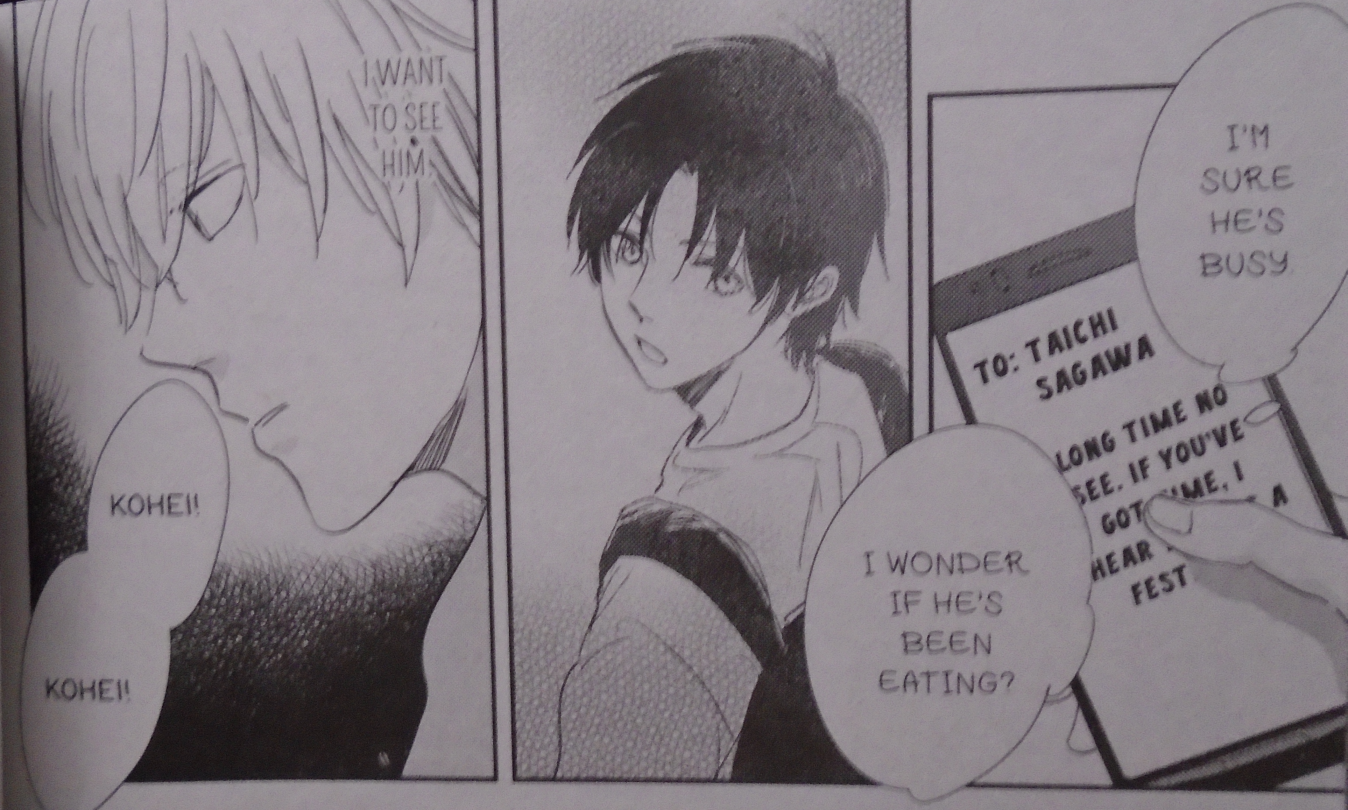

Kohei’s handsome appearance naturally attracts attention, especially from young women, and being hard of hearing makes people pity and idealize him. However, no one seems to notice that their instinctive delicacy around Kohei’s disability only isolates him and discourages him from embracing social activity. A youth typified by loss and ostracism has matured classmate Taichi into a considerate young man who understands the impact of treating people poorly due to circumstances beyond their control. So when Taichi meets Kohei, the partially deaf young man is surprised and intrigued to finally encounter someone who treats him as a normal person rather than a charity case or cause celeb. The emotional scars both young men carry with them make them hesitant to completely trust others, so Taichi & Kohei struggle to admit to themselves and each other that they complement each other and can & should be close, intimate friends.

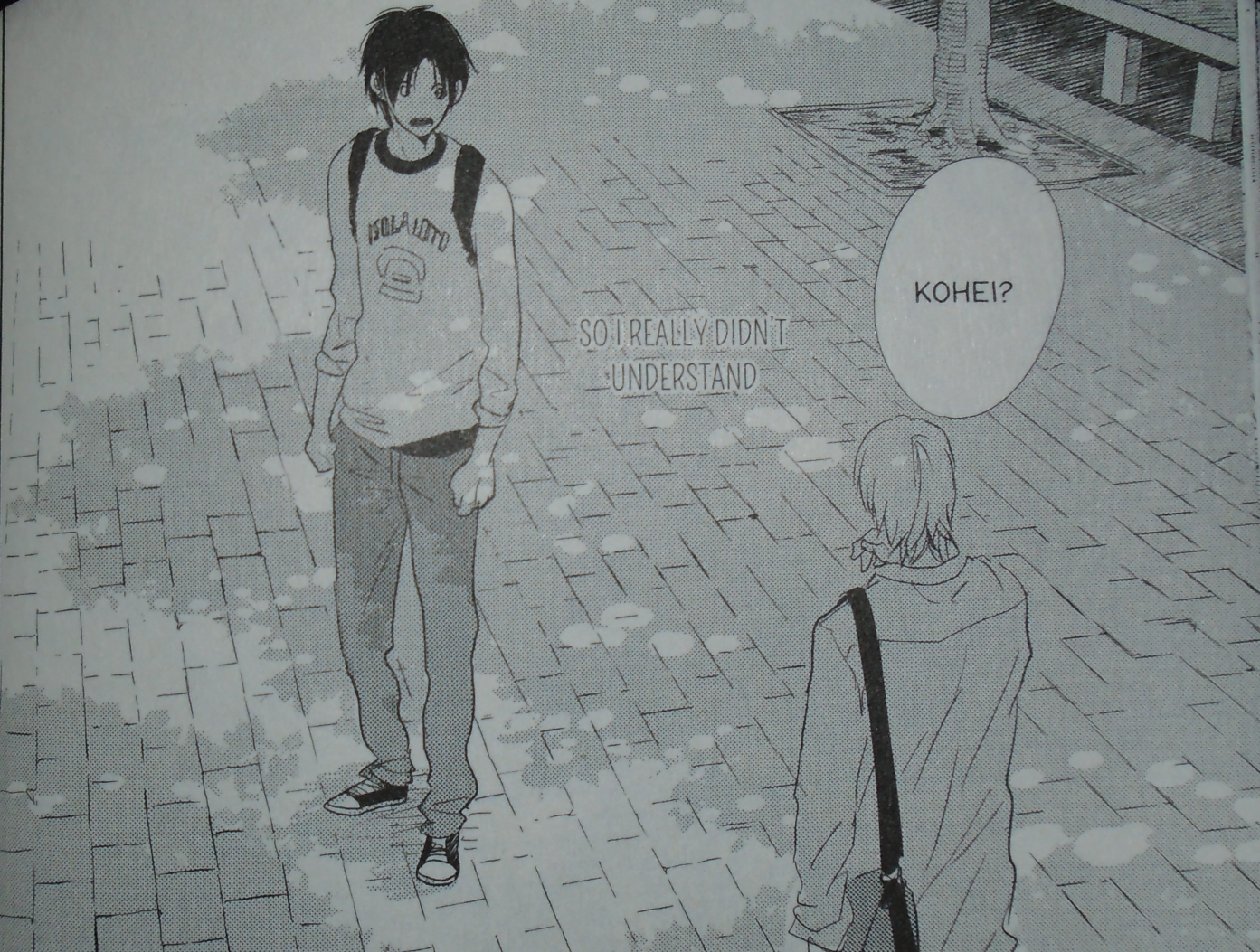

Fumino’s manga is a rich character study of two young men that are practically opposite sides of the same coin. Kohei has light-colored hair, comes from a solidly middle-class family, and is particularly introverted. Taichi is a dark haired poor orphan. Rather than accepting the role that life has planned for him, Taichi aggressively fights to assert himself, both literally and figuratively, never refusing opportunities and making both friends and enemies easily due to his outspoken personality. Both young men find a bit of themselves in the other, which both draws them together and frightens them as their vulnerabilities feel emotionally raw. The manga depicts these two young men meeting for the first time, struggling with the anxieties that their relationship causes, and ultimately admitting that each of their lives is richer with the other present.

The storytelling is steady and purposeful, always staying grounded in reality. So readers eagerly expecting a typical yaoi tale of seduction and sensuality may find I Hear the Sunspot rather dull. Readers intrigued by romantic manga revolving around physical disabilities, such as One Week Friends & A Silent Voice, may appreciate this book’s insightful observation of the way Japanese people instinctively treat individuals with handicaps. Kohei is typically marginalized by society as “one of those people,” someone who’s different and therefore needs to be treated with kid gloves. Although no one means harm, the people surrounding Kohei do unconsciously alienate him by stereotyping him as either a difficult person to deal with or someone who needs coddling and assistance.

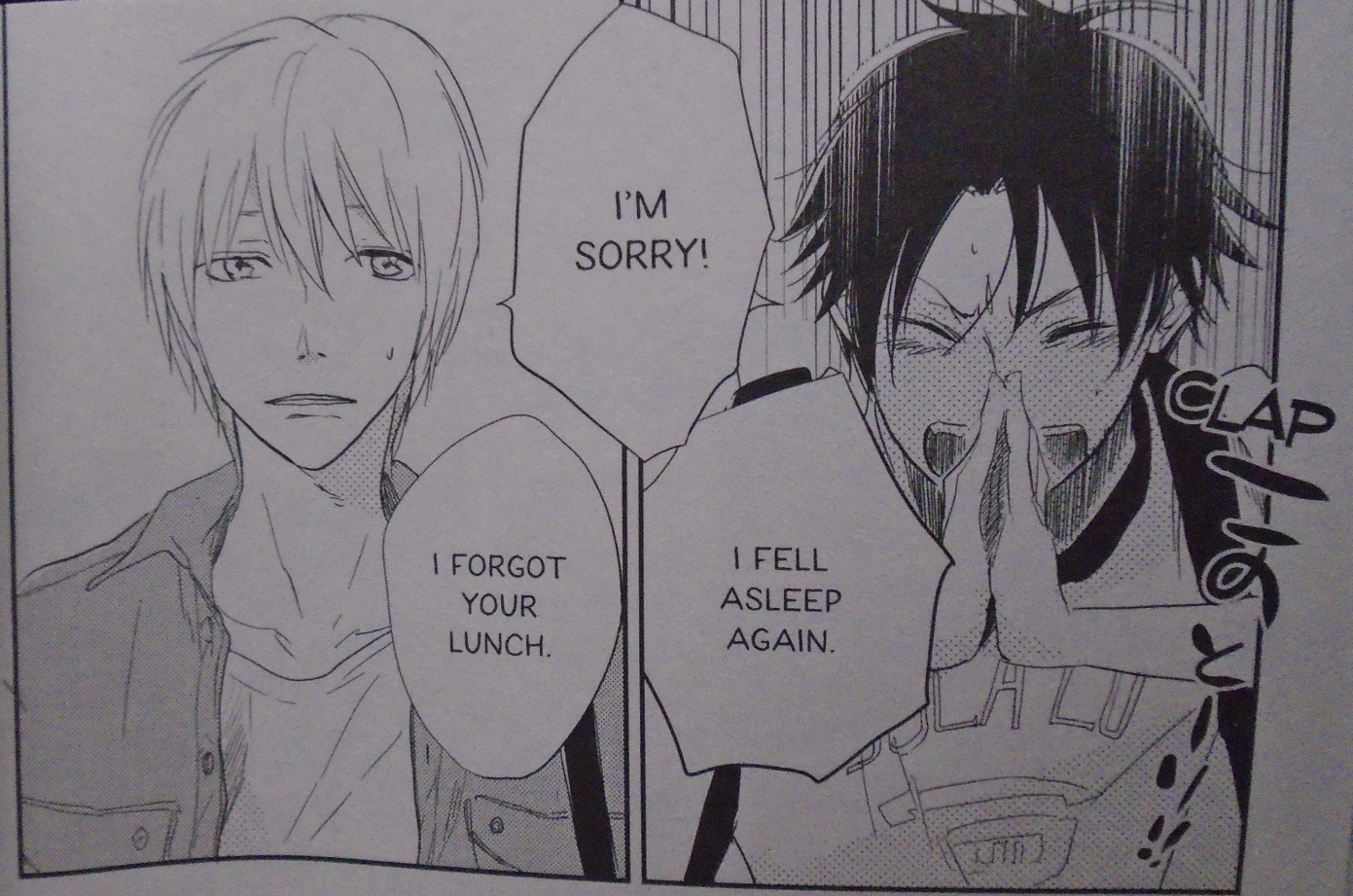

Fumino’s graphic art doesn’t feature prominent female characters but does exhibit the design aesthetic of typical shoujo manga. Pencil lines are thin and wispy. Detail isn’t photorealistic, but it is always substantial enough to create a familiar, realistic, everyday setting. Panel lay-out is easy to follow. With only a few exceptions, the placement of dialogue word balloons is clear enough to always distinguish who is speaking.

One Peace Books’ translation is lettered and typeset effectively to make reading easy. The text is free of errors and typos (granting one instance of “all right” spelled as “alright”). Personally, I was briefly distracted by the translation’s use of “antisocial” to describe Kohei. I personally think of “antisocial” in clinical terms as a reference to mildly psychotic behavior. The manga translation uses the term more casually to mean “unsociable.” Japanese signs and text are translated throughout the book. Sound effects are kept intact with unobtrusive translations. The 200 page book contains no overtly objectionable content: no adult language, nudity, or graphic sex.

Some readers may be drawn to Yuki Fumino’s original I Hear the Sunspot manga by awareness of or exposure to its 2017 Japanese live-action feature film adaptation. Other readers may be intrigued by the promise of a dramatic, realistic boy-love story starring a handicapped character. Potential readers should be forewarned that the first volume of I Hear the Sunspot, which does stand alone but also has, presently, two sequel volumes, is foremost a character drama about a deep friendship developing between two college boys. The story’s realism and emphasis on emotional vulnerability makes it compelling and heartfelt, albeit slow paced and naturalistic.